When the Citroën DS burst onto the European motoring scene 68 years ago, its high-tech spec revolutionised the saloon car sector

Words: Paul Guinness

It’s hard to over-emphasise the dramatic impact that the launch of the Citroën DS had on the motoring world when it was first unveiled in Paris in 1955. Take yourself back to that time and consider what Britain’s car makers were building in downtown Dagenham, Longbridge and Cowley. Ford was busy producing its charming but utterly conventional Mk1 Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac, while BMC’s saloon offerings included the Austin A90 Westminster and Morris Oxford Series II. Then Citroën came along and decided the whole family car market needed a shake-up.

Of course, this wasn’t the first time the world had been amazed by a new Citroën. The revolutionary front-wheel drive Traction Avant had shocked and impressed in equal measure when launched in 1934, while the debut of the Deux Chevaux in 1948 showed that Citroën hadn’t lost its knack when combining innovation and individuality with sheer practicality. Yet even a world that had previously experienced Citroën’s quirky approach to technology would still be shocked by what came next: the jaw-droppingly daring DS.

The idea of an all-new Citroën to replace the successful Traction Avant had been on the cards for many years, with the company ploughing immense amounts of time and resources into its VGD (Voiture de Grande Diffusion) project since before the outbreak of the Second World War. And yet it wasn’t until 1954 that the final shape of what was to become the new DS finally emerged from the studios of chief stylist Flaminio Bertoni, approved and signed off by Citroën management that same year.

So futuristic looking was Citroën’s pre-production prototype, it seemed almost inconceivable that anything less than revolutionary would be fitted under the bonnet. Indeed, Citroën’s engineers had been experimenting with an all-new fuel-injected flat-six engine since 1950, developing it in both water- and air-cooled guises before deciding that the latter simply wasn’t refined enough for the market sector at which the DS would be aimed. The water-cooled version, meanwhile, suffered from lack of power and severe overheating problems, while development of its fuel injection system wasn’t progressing as planned.

The solution was to fit the 1911cc four-cylinder engine from the Traction Avant instead – a controversial but understandable decision, despite the fact this engine dated back to 1934. It may have caused consternation within Citroën that such an aged (and not particularly refined) engine should be installed in a brand new car intended to be the most futuristic in its sector, but let’s not forget the cost implications involved at the time. Development of a brand new powerplant was an expensive business even then, and the lengthy gestation period of the DS was costing Citroën serious money. The company had learned its lesson with the costly development of the Traction Avant in the 1930s (so expensive that the company went into liquidation in 1934, the year of the new model’s launch, only to be rescued via a takeover by Michelin), and it wasn’t about to make the same mistake again.

In any case, the engine of the DS might have been old, but every other aspect of its technology was light years ahead of the competition – not least its incredible and unique hydraulics powering the DS’s suspension, clutch, transmission and steering. Even the structure of the car was unusual, its skeletal design having bolt-on body panels attached for ease of construction and repair. And of course, the panels themselves weren’t run of the mill either, with the bonnet being made of lightweight aluminium and the roof section constructed from a glassfibre and polyester mix.

Despite the fact that the DS had been in development for an inordinately long time, its motor show debut (Paris Salon, 1955) was an almost rushed affair. Spy photographs of the pre-production DS were starting to appear in the world’s press, which meant Citroën faced losing some of the newcomer’s impact if the launch wasn’t imminent. And so, on October 5 that year, Citroen’s Traction Avant-replacing DS made its official debut.

Even the most optimistic of Citroën insiders couldn’t have predicted the extraordinary response to the DS. It seems those blurred spy photographs that had appeared on the front page of every French newspaper had actually worked in Citroën’s favour, adding to the sense of expectation. When the covers came off the official production version in Paris, the show stand was mobbed by an excited public desperate for its first glance of the newcomer.

Just an hour after the opening of the 1955 Paris Salon, in fact, an incredible 700 orders had been placed for the DS. And by the close of business on that first day, the figure had reached more than 12,000 – a world record for any motor show debut at the time, and proof that Citroën was providing customers with exactly the car they wanted. The DS couldn’t have got off to a better start.

Like so many initial success stories, however, the DS wasn’t without its troubles. The car had been in development for an unusually long time, which meant any potential problem areas should have been ironed out long before it went on sale. But let’s not forget that the overall style and the final technical make-up of the DS wasn’t formalised until very late in its development cycle, which left engineers precious little time to make sure it was as reliable as it was technically impressive.

Another problem was that Citroën wasn’t yet ready for full-scale DS production, which meant a mere 1000 examples rolling off the line during its first six months on sale. That figure equated to just eight per cent of the orders from day one of the Paris Salon being satisfied during the car’s first half-year on sale, and prospective buyers were understandably frustrated.

Reliability was a key issue too, with the DS soon gaining a reputation for fragility; many owners of early examples were angered by their cars’ frequent breakdowns and general lack of dependability. And once your DS had let you down, you then faced the frustration of poor after-sales back-up, with most Citroën technicians unsure of their way around the DS and its various complexities, largely due to a lack of training by Citroën itself. After such a glittering motor show debut, the first year of life for the DS was troubled, and as a result the car soon started generating negative headlines and its reputation began to sink. Drastic action was needed if one of the most promising, most exciting new cars of the 1950s wasn’t to suffer a sales and image disaster.

Fortunately such a disaster was averted thanks to a major quality control initiative introduced by Citroën, ensuring that build quality was greatly improved and the DS emerged as a dependable and reliable car at last – a reputation improved still further once the company decided to enter the world of motorsport in the late ’50s, with the DS becoming one of the most unlikely rally stars of its day.

The company also focused on expanding the DS line-up, with a cheaper new derivative (the ID19, with hydraulics operating only the suspension system) arriving in 1956, followed by the all-important Safari (estate) in 1959. The luxurious new DS Pallas arrived in 1964, taking the brand further upmarket, followed by the limousine-like DS Prestige – complete with separate chauffeur division and intercom system for any rear-seated VIPs.

Crucially, 1966 saw the DS’s original red hydraulic fluid replaced by a new green fluid, designed to reduce the previous corrosive qualities that had caused problems with the DS’s hydropneumatics. And as the years went by, the DS engine situation improved, with a five-bearing 1985cc unit arriving in 1966, followed by 2175cc and 2347cc alternatives for extra power and refinement.

From an onlooker’s point of view, however, the biggest DS change occurred in 1967 when the whole front end was redesigned, losing its original headlamp design and incorporating a sleek new look with glass headlamp covers. Famously, the headlamps themselves turned with the steering on Pallas models, adding further to the DS’s reputation for technological achievement.

It was through this ongoing development programme that the DS managed to remain not just competitive but still ahead of its time. Even when the last example was produced in 1975, a full 20 years after the original’s debut, the DS was still seen as an extraordinary machine, technically superior to many a car a fraction of its age.

Yet it will always be the sheer beauty of the DS that will continue to endear it to large numbers of enthusiasts, which helps explain why it is now so sought after on the classic scene – and why values have been rising over the last decade. After the highs and lows of its first few months of life, the enduring charm, character and sheer technical wizardry of the DS are as appealing now as they were nearly 70 years ago.

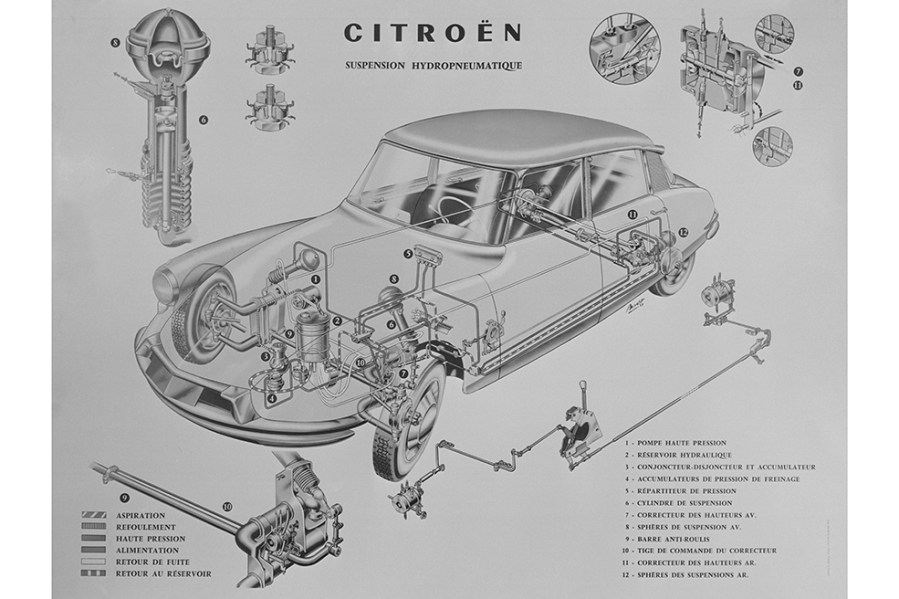

Hydropneumatic suspension

By the standards of 1955, the hydraulic system used for the Citroën DS was truly revolutionary. Where previously hydraulics had generally been restricted to use in brakes and power steering, the DS employed them in its suspension, clutch and transmission systems.

The suspension set-up was particularly fascinating. Each of the DS’s wheels was connected to a hydraulic suspension unit consisting of a sphere containing pressurised nitrogen, a cylinder containing hydraulic fluid screwed to the suspension sphere, a piston inside the cylinder connected by levers to the suspension itself, and a damper valve between the piston and the sphere. A membrane in the sphere prevented the nitrogen from escaping, while the motion of the wheels translated to a motion of the piston, which acted on the oil in the nitrogen cushion and provided the spring effect.

The hydraulic cylinder was fed with hydraulic fluid from the main pressure reservoir via a height corrector – a valve controlled by the mid-position of the anti-roll bar. If the suspension was too low, the height corrector introduced high-pressure fluid; if it was too high, it released fluid back to the fluid reservoir, thereby maintaining a constant height. Meanwhile, a control inside the car allowed the driver to select one of five heights, comprising the normal riding height, a pair of higher-riding levels for poor terrain and two extreme positions for changing wheels.

Hydraulics also played a part when it came to the DS’s clutch and transmission, for while the mechanicals of each were relatively conventional, fitment of a hydraulic gear selector meant the speed of engagement of the clutch was controlled by a centrifugal regulator that sensed engine revs and was driven off the camshaft by a belt.

The braking system was equally clever, with the engine idle speed dropping to a revs-per-minute figure below the clutch engagement speed every time the brake pedal was pressed, thereby preventing friction while stationary and in gear.

Racing pedigree

The Citroën DS wasn’t perhaps the most obvious choice when it came to creating a world-beating rally car. Its complex technology in general and hydropneumatic suspension in particular meant a whole range of unusual challenges for the Citroën engineers tasked with launching a new rally star.

So, what caused Citroën to take the DS rallying in the first place? Numerous benefits, including the major publicity that would be generated by success on the world rally stage. Even more importantly, however, any car capable of winning rallies could have its public image transformed – and after the DS’s initial reliability issues, emphasising the model’s durability was seen as vital.

Citroën’s official DS rally cars proved very competitive, winning some of the rally world’s most coveted trophies between 1959 and ’73 – including the European Championship in 1959, plus victory in the all-important Monte Carlo Rally in both 1959 and 1966. That latter win, however, was a controversial one, coming about after the first, second and third placed Mini Coopers were all disqualified (along with the Lotus Cortina that finished fourth) on a technicality, leaving Citroën DS19 driver Pauli Toivonen to be crowned the official 1966 winner.

Meanwhile, numerous DS rally drivers ended up benefiting from the model’s technical make-up. These included Bjorn Waldegaard, who while taking part in the 1972 Chamonix Winter Circuit, ended up losing a tyre, which came away from the rim completely. Although this would have caused many a lesser car to retire, Waldegaard simply raised his DS’s suspension to its highest setting and completed the rally on three wheels.

The most beautiful car in the world

When a panel of some of the world’s most influential car designers was asked to name the most beautiful car in the world, you might have expected a supercar legend from the likes of Bugatti, Ferrari or Aston Martin to make it to the top spot. But you’d be wrong. Names like Ian Callum (famous for his Jaguar and Aston Martin designs), Leonardo Fioravanti (of Pininfarina/Ferrari fame) and ItalDesign founder Giorgetto Giugiaro were all part of the assembled jury some years back. And their verdict? First place went to the Citroën DS.

It seems that when it comes to sheer beauty, those in the know adore the DS more than the Jaguar XK120 (in second place), Ferrari 275GTB (third), Jaguar E-type (seventh) or original Lotus Elan (ninth). By any standards, that’s a remarkable achievement.