It’s a misty October day when we visit the villa. Opening the gate, we’re greeted by a sloping pebbled path lined on either side by roses. It functions as a sort of cue, directing the eye ahead to what we’ve all come to see: architect Andrea Palladio’s Villa Almerico Capra, detta “La Rotonda,” the basis for Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and perhaps Palladio’s own capolavoro.

We are initially stunned by the aspects we knew to expect—the villa’s pleasing Vitruvian proportions, its four identical facades, its flattened dome, based on the Pantheon, the fact that, as Palladio expert Roberta Parlato told us, “it’s all clear. You understand immediately where you have to go.”

And yet, like any piece of art, it is what we don’t expect that stuns more. Our tour guide, Emma De Puti, urges us to turn our gaze towards the steps that flank each side of the house. We are standing on one of the porches, looking from above at the expanse through the columns. But as we tilt our eyes to the ground, instead of the steps we know to exist, we see only grass and air. It is as if the building simply stops at the end of the porch.

At this realization, we all gasp almost involuntarily, stunned by how effective this illusion is, even if we know it is exactly that. One time, De Puti told us, a visitor to La Rotonda actually panicked, so persuaded by the illusion that she thought there really were no stairs. She wanted to know: How do I get down?

This is the power of Palladio—his work makes the fantasy so convincing that, for a second, it becomes reality.

Photo courtesy of Angel de los Rios

To understand Palladio, we have to understand his humble beginnings as a stonemason and how much he was a child of Veneto; he was born in Padova in 1508 and died in Vicenza in 1580. Yet he went on to become one of the leading architects of the Renaissance, influential both inside and outside of Italy.

We’re on this tour in Vicenza thanks to Exploro, an initiative meant to expose travelers and residents alike to the area’s jewels. When people think of Vicenza, they think of Palladio. His impact was so far-reaching that he was even named by Congress in 2010 as “the father of American architecture,” despite dying almost 200 years before the country’s independence.

His path to becoming an architect was not assured. While working on the rebuild of a villa outside of Vicenza, the stately home’s wealthy patron, Count Gian Giorgio Trissino, took notice of Palladio, then called Andrea di Pietro della Gondola. He offered him a Humanist education, steeped in part in the understanding of Roman architect Vitruvius’ principles, which hinge on physical strength, utility, and an almost heavenly idea of proportion. Essentially, a building had to be all things—sturdy, clearly laid out for its use, and beautiful—to follow the standards of Vitruvius. As if to confirm the divine nature of architectural beauty, the count even gave Palladio his new name, calling him thus in reference to Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and warfare. By the time Palladio had really cemented his new career, he was almost 30, an age that would have been viewed as quite late to begin, according to Parlato. (We might breathe a sigh of relief that the same is not true now.)

Villa Godi Malinverni

The architect would design and construct his first villa in 1542, Villa Godi Malinverni, a sumptuous country house surrounded by gardens and nestled in the hills. That structure, inspired in large part by the count’s own Villa Trissino, encompassed much of what would go on to be quintessential Palladio, like the symmetrical wings on either side of a building for agricultural use, known as barchesse, and the walled courtyard near the house’s entrance.

Basilica of Vicenza

But it wasn’t Villa Godi that was the key to Palladio’s future success, despite its obvious beauty, Parlato tells us. It was likely the Basilica of Vicenza, a major architectural commission Palladio was awarded in 1546. The project itself was a redesign of a 15th-century court—it would serve as the city’s main governmental building. Parlato called the building the “turning point of his career” and, fittingly, has since been referred to as the Basilica Palladiana. His ingenious plan was to wrap the underlying Gothic structure—characterized by its pointed arches—with an exterior of marble arcaded loggias. Builders literally went arch by arch, which meant the building took almost 70 years to complete.

Ponte degli Alpini

By the end of his life, Palladio was known as an expert builder of both private villas in the Veneto countryside and public structures, like the famous wooden Ponte degli Alpini in Bassano del Grappa and Vicenza’s Teatro Olimpico, his final work before his death. But it is still the Villa La Rotonda that lives most of all in the public consciousness.

Like most noble villas, the commission of the house itself is a fascinating story: the owner was Paolo Almerico, a priest and former secretary of two Popes who, near the end of his life, decided to return to Vicenza to be closer to his family. Despite having children (and that despite being a priest), Almerico envisioned the villa as a place in which only he would reside.

“Almerico wanted to celebrate himself building this house, and to build this house, he called the architect that at that moment was at the top of his career,” De Puti said. That was Palladio.

Palladio began work on Villa La Rotonda in 1565, but it was not completed before his death in 1580. In fact, it was his protégé, Vincenzo Scamozzi, who was tasked with finishing the villa’s now-iconic dome. Like most architects, he, too, wanted to leave his mark on the building. So instead of using Palladio’s design, a dome resembling “half of a sphere,” Scamozzi gave the top its distinctive flatter shape. At the time, the oculus of the dome was actually open, like the Pantheon, and water would trickle—purposefully—into the center of the house.

Villa La Rotonda

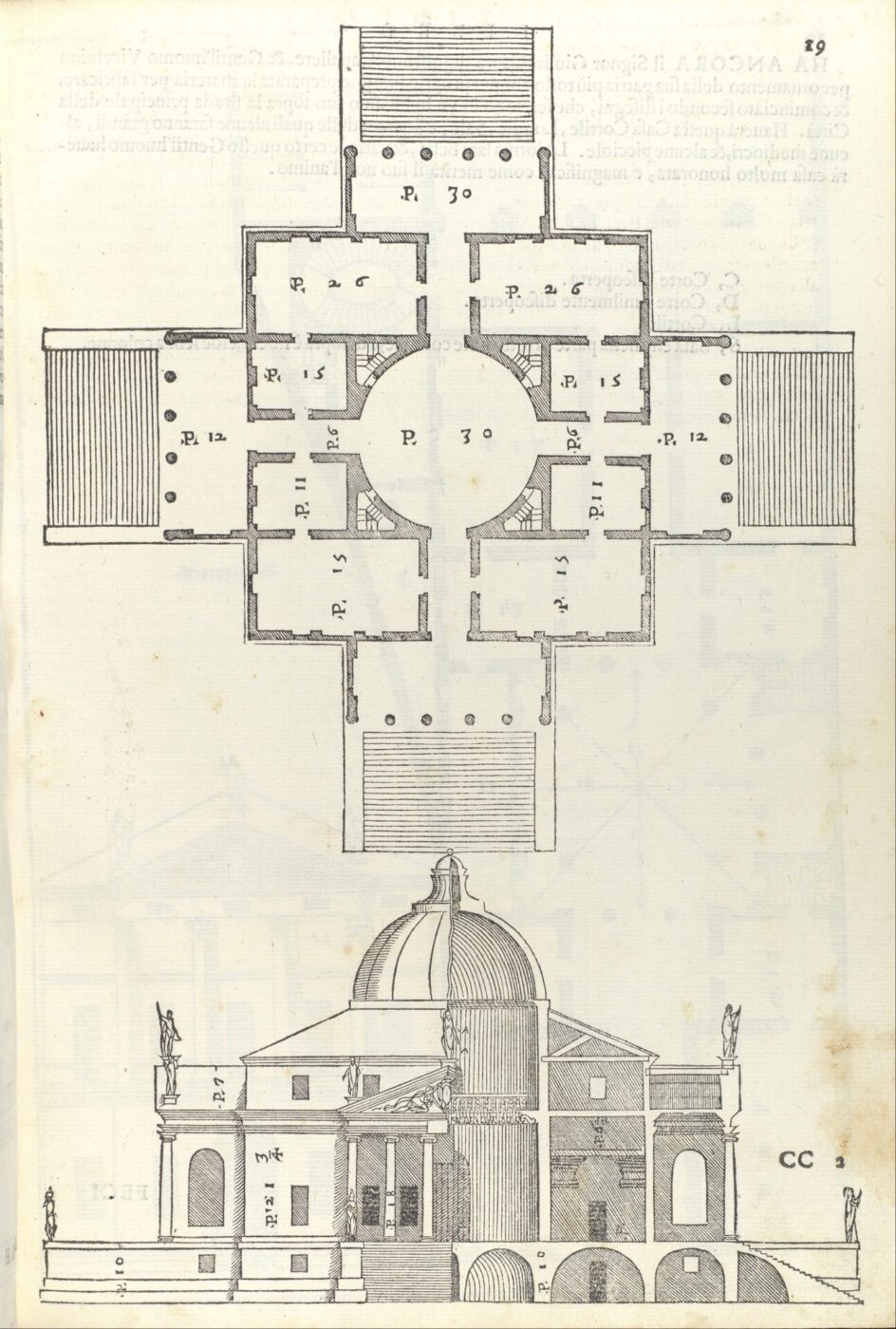

Plans of the house show how clearly symmetrical and ordered it was. Palladio’s design—a cube with a rectangular room at each corner and a circular room in its center that housed the dome—creates a sense of immediate geometry when entering the space. The four corner rooms were considered multi-use: depending on the season and temperature, the furniture could be moved around and any of the four rooms could be used as dining rooms.

In 1591, the Capra family purchased the building after Almerico’s death. Sixteen generations of that family lived in the villa until 1912, when it was bought by the Valmarana family, who owns and maintains it still today.

Over the centuries, the villa attracted many famous visitors, including German novelist, poet, and public intellectual Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose time in Italy is well-documented. Upon seeing the villa for the first time in the flesh, Goethe was struck by its genius:

“Maybe the architectural art has never reached such a level of magnificence.”

But Palladio’s lasting legacy is felt perhaps most keenly in the I Quattro Libri Dell’Architettura, his magnum opus on architecture that functions as a sort of textbook for the aspiring architect. Based in part on Vitruvius’ ideals, each book has its own theme: materials and architectural orders, private town houses and country estates, public buildings, and ancient Roman temples, referencing both his own work and ancient Roman structures as examples. First-edition copies of the books reside in, among other places, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Morgan Library and Museum.

What made the books so innovative was their simplicity, Parlato said.

“That book is not the only book about architecture from the Renaissance, but if we compare it to the others, his book is very clear,” she said. “You don’t need to be an architect to understand it, especially the pages that refer to his buildings. There’s the plan, the front sometimes and then a very short text, which is very easy to understand.”

Another academic, Guido Beltramini, the director of the Palladio Museum in Vicenza, noted the larger implications of Palladio’s four books in a 2017 interview with The New York Times’ Elisabetta Povoledo.

“His four books are a manual to change the world,” he said, “not a catalog of projects, but an instruction manual teaching us to create something beautiful, useful, and at little cost; the Ikea method, we could call it.”

Photo of Monticello courtesy of Library of Congress

While Jefferson is the Palladio acolyte that gets the most attention in the United States, it was British architect Inigo Jones who first disseminated the Quattro Libri at large throughout Europe. Born in 1573, Jones visited Italy in the early 1600s, not long after Palladio’s death, with a copy of the book. He came to Vicenza and saw La Rotonda—his copy of the four books with his marginalia is now kept at Oxford University’s Worcester College.

But Palladio reached America in large part through Jefferson, who came to the Piedmont region of Italy in 1787 but never actually traveled to Veneto and Vicenza. He never saw Villa La Rotonda but was inspired by what he read in the Quattro Libri. Palladio described the villa as “a house that rose on the hill,” which is what Jefferson used to give his house, Monticello, or little hill, its name.

Jefferson’s own interest in architecture began, at least according to the myth, with his purchase of a pattern book by English architect James Gibbs from a “drunken cabinet-maker in Williamsburg” while the eventual third U.S. president was studying at the College of William & Mary. Even in retirement, Jefferson was so tied to books as his architectural guide that, when asked to design a house later in life, he refused—he had already sold his books to the Library of Congress, said Gardiner Hallock, interim president of Monticello.

“He thought Palladio came closest to recording the original Roman example,” Hallock said.

It was also the proportions of Palladio that attracted Jefferson. Even in some of his earliest work at Monticello, he adhered quite closely to the specific room sizes, ceiling heights, and exterior guidance from Palladio. Yet the first truly neo-Palladian building in the United States was not actually Jefferson’s home, but Drayton Hall, a stately manor in Charleston, South Carolina, built in 1738. While the architect of the plantation is not known, it is clear from the owner, John Drayton’s, personal library that he owned Palladio’s four books, as well as those of Gibbs and William Kent’s Designs of Inigo Jones. Jefferson may have been the person most closely associated with the popularity of Palladian ideals in the United States, but he was certainly not the first or only to use the Italian architect’s work as a manual.

“[Palladio’s] is an architecture easy to replicate but not with the same results,” Parlato said.

Virginia Capitol, designed by Jefferson in the 1780s

It was the Virginia Capitol, however, that would solidify Neoclassicism as the state and federal architecture of choice. Designed by Jefferson in the 1780s, the statehouse took its inspiration in part from Greek and Roman temples, like the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

“[Jefferson] proposed it as a model for the statehouse government building,” Hallock said. “It was the first Classical building. And it just becomes what people do for their state Capitols and for federal architecture in Washington, D.C.”

This, of course, would go on to inspire such prominent examples as the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the Supreme Court. The question is whether Jefferson’s choice to use Palladio and Neoclassical architecture was solely aesthetic or also political. We might argue that any choice of architecture is inherently political.

“For Jefferson, it was not only establishing a seat of power and of social standing, but a way to improve the status of the country as a whole,” Hallock said. “Many Europeans saw the United States as a backwater, but by building these prominent buildings using sources which were well-respected in Europe, accessible because it’s written in a book, it was a way to rise above the idea of a young United States full of savages and unlearned buffoons.”

Jefferson was known as saying to his friends that Palladio was the “Bible: you should get it and stick close to it.”

But if Palladio is the architectural Bible, he is one with an easy entry-point, accessible to all, clear, able to be understood. Each of the rooms work in concert with the other. Even the height of the ceilings is relative to the dimensions of the room.

And while we may have illusions of grandeur when we think of the Neoclassical style, associating it with some of America’s most prominent political buildings, Palladio’s villas are revolutionary in some ways because they are a study in contrast. When Parlato brings guests to Palladian villas, they are struck by how livable they seem. An imposing and cold manor, they are not. At a villa like La Rotonda, a visitor might say: Now that could really be a home.