A towering scholar-turned-diplomat, public intellectual

Harvard faculty examine legacy of Henry Kissinger

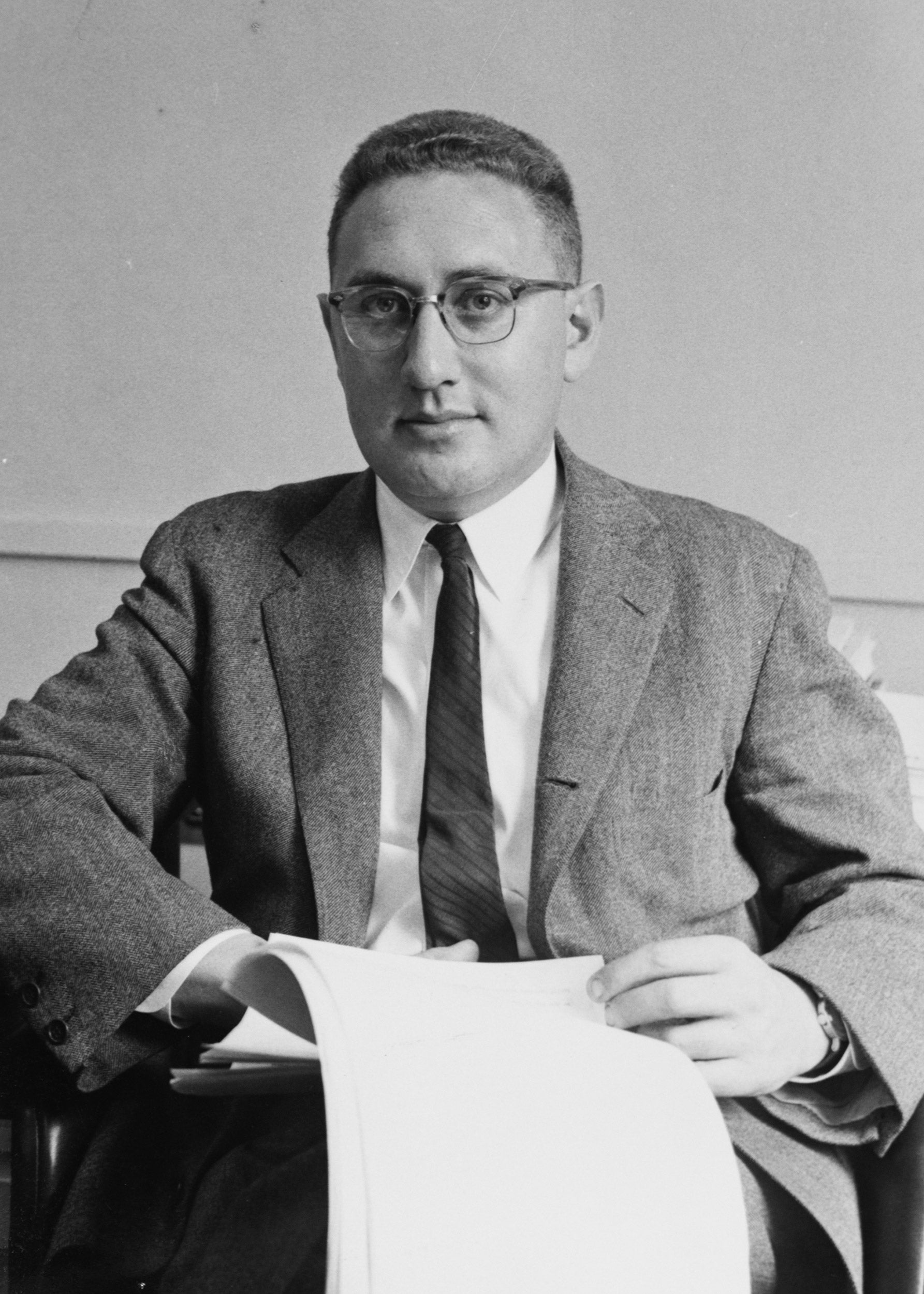

A 1959 portrait of Harvard faculty Henry Kissinger.

Harvard file photo

Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whose Harvard education informed 70 years as a diplomat, adviser to presidents, and public intellectual, died Wednesday at age 100.

Born Heinz Alfred Kissinger in 1923 in Bavaria, he and his family fled Nazi Germany in 1938, settling in New York City, where 15-year-old Heinz became Henry. Kissinger finished high school and attended the City College of New York part-time before entering the U.S. Army and serving in Europe during World War II.

Kissinger completed his undergraduate degree at Harvard College, where he lived at Adams House. He graduated summa cum laude in 1950 with a bachelor’s in political science, then earned a master’s in 1951 and a Ph.D. in 1954. In 1951, Kissinger joined the Government Department faculty, where he remained for two decades.

In that period Kissinger began to assume what would become a decades-long role as an adviser to the State Department, think tanks, defense contractors, and a string of politicians and diplomats from Republican Nelson Rockefeller to Democrat Hillary Clinton. He became known as a foreign-policy “realist” — an approach that would leave him with a complicated legacy — and for his robust support for U.S. military interventions and anti-communist movements in Latin America and elsewhere.

Kissinger emerged as an unlikely celebrity during the Nixon and Ford administrations, in which he served as national security adviser and secretary of state. He helped open up U.S. relations with China, achieved détente with the Soviet Union, and negotiated an end to the Vietnam War. Kissinger won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 for his work in Vietnam, but critics pointed to his authorization of the secret carpet bombing of Cambodia and argued he potentially could have ended the war sooner.

Kissinger, who had taken a leave of absence from the University beginning in 1967 to serve in government, resigned in 1971. After his career in government he would go on to launch a consultancy in Washington, D.C., and write numerous books on China, diplomacy, nuclear weapons, and even artificial intelligence.

Harvard faculty, including some who knew Kissinger, shared their thoughts on his legacy with the Gazette. Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Graham Allison

Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at Harvard Kennedy School

Assistant Secretary of Defense during Clinton administration, founding dean of HKS

I enrolled in his class at Harvard 58 years ago — Gov 180. It was a legendary course on the principles of international relations. It had been a storied course at Harvard taught (before Henry began teaching it) by McGeorge Bundy, who was dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and who, in 1961, left for Washington and became Kennedy’s National Security Adviser. For Henry, this was like a great promotion to wear Bundy’s mantle. That was part of what raised his horizons to the notion that, “Heck, maybe I could become national security adviser.”

Henry, as he was often quite proud to say, basically became the person he was at Harvard. Even though he had a complicated history with Harvard, he never forgot the fact that Harvard was where he grew up to be somebody who could think about the world. Harvard opened his mind and excited his curiosity and created all the opportunities he elicited and enjoyed. This was the most formative chapter in his intellectual odyssey.

He was complicated, demanding. I became his course assistant for that course and then for the graduate course, and then, sometimes his research assistant. When he went to Washington in ’69, I had just become an assistant professor, and so I declined to go because I was hoping to become a professor. But I agreed to consult with him and another faculty member who worked for him directly, Morton Halperin, whom I was friendly with.

After that, he and I had the good fortune to collaborate on a series of joint activities, including this piece he and I published in Foreign Affairs last month on the road to AI arms control. One of the amazing things about him was, here’s a guy, when he was 95 or 96, AI dawned on him. He said, “Graham, this is the most exciting intellectual and challenging thing I’ve ever seen!”

He would bring to a problem a large strategic point of view grounded in a lengthy historical perspective. I wrote a piece in The Atlantic five or six years ago on Kissinger as an applied historian or Kissinger as the model of statecraft as applied history.

Henry Kissinger with Joseph Nye (left) and Graham Allison during a 2012 discussion at Harvard’s Sanders Theatre.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Joseph S. Nye Jr.

Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor, Emeritus

Former Dean of HKS, 1995-2004

I’ve just written an essay for Foreign Affairs summing up his legacy in moral terms — it’s a mixed record. The three big accomplishments were the opening to China; the detente with the Soviet Union and arms control; and the Middle East peace process, which goes back to the ’73 Yom Kippur War. Those are all masterful diplomatic strokes.

On the negative side of his ledger [is] the overthrow of the Allende government in Chile; the backing of Pakistan’s massive brutality against Bangladeshis and Bengalis in the early ’70s — some people would add East Timor, where he supported the government. But the biggest of all is Vietnam [and] the bombing of Cambodia, which led to Pol Pot coming in with a genocidal regime. And then, the way that war ended, which is more controversial. Some people thought they ended it well. Other people thought no, you could have gotten out sooner with far fewer lives lost. My view is that they could have ended sooner with far less loss of lives, both American and Vietnamese, but Barry Gewen, who recently wrote a book on Kissinger, or Niall Ferguson, who also recently wrote on Kissinger, would take a different view.

Henry was very good at working the press, and he had a very strong instinct for power. And I think those two characteristics allowed him to get a lot of attention. Once you’ve got a lot of attention, then presidents want to be seen with you. Also, to be fair, Henry had good ideas. If you say, “There are a lot of people with good ideas. Why him?” Those are the reasons.

His books ought to be mentioned because his books are quite good. People remember him as a realist, but he also wrote in one of his books on world order that power alone is not enough. You also have to have legitimacy. So, it’s largely true that he was a realist, but it’s also true that he understood the importance of legitimacy.

Fredrik Logevall

Laurence D. Belfer Professor of International Affairs at HKS and Professor of History at Harvard

There is no question that Henry Kissinger ranks as a hugely consequential figure in the modern history of U.S. foreign policy. Sometimes he overshadows Richard Nixon in scholarly assessments more than he should — the so-called opening to China, for example, I would say was more Nixon’s doing than Kissinger’s, as Kissinger was initially a skeptic on the endeavor.

But the various major policy initiatives in the period 1969-1976 certainly bear his imprint in vital ways. A key contribution, it seems to me, was his recognition that containment — the broad strategy the U.S. followed in the Cold War — allowed little room for diplomacy until the guys in the white hats could claim the surrender of the guys in the black hats. In other words, the propensity of Americans to view all adversaries as equally wicked and degenerate rendered negotiations morally suspect a priori.

Kissinger (and Nixon) rightly saw the problems with this outlook and pushed beyond it. The result was important progress toward détente with the Soviet Union and rapprochement with China.

But there were serious limits to the Kissingerian approach. His fixation on superpower relations and great-power politics led to him neglect huge swaths of the world or to see them as significant only to the extent that they influenced relations among the top powers.

As part of his legacy we must therefore consider, for example, his lack of concern for human rights; his role in the toppling of Chile’s democratically elected leader, Salvador Allende; his espousal of secret bombing campaigns in Southeast Asia; and his willingness to follow Nixon’s proclivity (as captured vividly on the White House tapes) to let partisan politics and re-election concerns shape foreign policy, including with respect to negotiations to end the Vietnam War.