Relatives of four Dutch children killed by the Nazis have described their sadness after being told their identity tags were found in the ruins of a death camp.

The extermination camp at Sobibor, in Nazi-occupied Poland, was established in March 1942 and shut down in late 1943 following a prisoners’ uprising. Some 250,000 Jews died there, according to the World Holocaust Remembrance Center at Yad Vashem.

Following the German invasion of the Netherlands in 1940, some 107,000 Jews were deported from the country, mostly to Auschwitz and Sobibor, where they were murdered.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), less than 25% of Dutch Jewry survived.

Among the dead were two uncles of Yoram Haimi, the Israeli archaeologist who spent 10 years excavating the Sobibor site alongside fellow archaeologists Wojciech Mazurek from Poland and Ivar Schute from Holland. Together they discovered metal identity tags belonging to four Jewish children.

The discovery made headlines last year as the tags appeared to have been made not by the authorities, but relatives concerned about becoming separated.

Now housed at the State Museum at Majdanek, Poland, the tags were engraved with names, dates of birth and addresses for Deddie Zak, Annie Kapper, David Van Der Velde and Lea Judith De La Penha.

Relatives of Deddie and Lea were located before the discoveries were publicly announced last January, but no trace of Annie and David’s families was found – until now.

This month, researchers from genealogy site MyHeritage tracked down their closest living relatives in the US.

Roi Mandel, director of research at MyHeritage, used archives and family trees to join the dots.

He told CNN: “I felt it was my duty to find the living relatives of Annie and David, to tell them what was found in the damned Sobibor land and to hear from them the story of their almost extinct family. They are the only branches left of the huge family trees and they will have a duty to tell the story of these children to future generations.”

‘Makes him a real person’

Brother and sister Sheryl and Rick Kool are second cousins once removed of David – his grandmother was their great-grandfather’s sister.

The Kools, whose parents were born in the Netherlands, knew many of their family perished, but were unaware of David, who died aged 10.

Sheryl, who lives in Seattle, told CNN: “I was very surprised because I knew nothing about David and that part of the family.”

She added: “The Holocaust was so dehumanizing. So to have a specific name and a concrete symbol of his life, it just makes him a real person.

“It’s obviously sad but gratifying to have more information and to put more pieces of the puzzle together.”

Her brother, who lives in Canada, told CNN: “David’s name tag has reminded me of the grief that my grandmother and so many others, who by luck or intent managed to avoid the fate of their murdered family members, must have carried with them to the end of their days.”

‘A voice from beyond the grave’

Annie’s aluminum tag was found near a mass grave. Her family was sent to Sobibor on March 30, 1943. When the train arrived three days later, all 1,255 passengers were sent to the gas chambers. Annie was 12 years old.

MyHeritage tracked down Annie’s second cousin Marc Draisen in Boston. Annie’s father Meijer was a first cousin of his mother Tilly.

“It was like having a voice from beyond the grave,” Draisen told CNN.

Draisen, who has never seen a picture of Annie, said: “The parents, in creating this name tag, were desperately trying to maintain their daughter’s identity and some hope of survival which of course didn’t come to pass.”

Mandel’s timing was eerily poignant, said Draisen. “My wife did a little research and soon learned Annie’s birthday was January 9 – the very day MyHeritage contacted me. She would have been 91.”

In the wake of the 1943 uprising, the Germans dismantled the camp. The site was plowed over and planted with a pine forest, according to the USHMM.

Haimi told CNN the excavation, which began in 2007, revealed the site of the gas chambers.

“There were eight rooms, 350 square meters of killing – 800 to 900 victims in six to seven minutes,” he said.

The excavation revealed 80,000 artifacts including shoes, jewelry, dentures, wallets and cutlery, Haimi added.

Welcoming the revelations, Haimi said: “Where there are relatives still alive they might have some information about those kids. We want their stories to be told.”

‘Deddie is my angel’

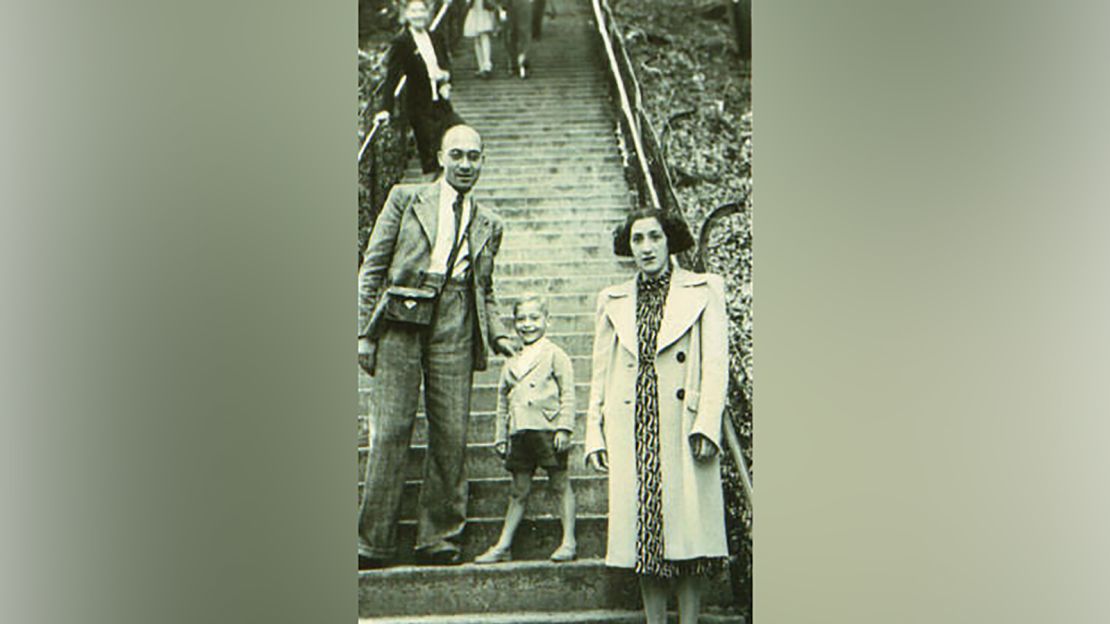

Lies Caransa traveled to Sobibor with her son in 2013, after learning of the tag belonging to Deddie – her first cousin. The pair grew close after spending much together at their grandparents’ home.

Being not quite 4, Caransa was taken to a creche when her family was rounded up in 1943. Her mother survived Auschwitz, but she never saw Deddie – then aged 8 – her aunt, uncle or grandparents again.

Now 82 and still living in Amsterdam, Caransa told CNN: “Because I possess nothing of him, it came as a shock – but it came also as a sign from heaven.

“I always thought I had a guardian angel on my shoulder because many times I was dangerously ill but always recovered. I think Deddie is my angel.”

Caransa was given a replica of the tag as Polish law dictates all archaeological finds belong to the state. Nevertheless, she has spent years fighting for the original – but to no avail.

“I have no brothers, no sisters, no aunts, no uncles and my mother died long ago. So I hope to have it back before I die,” she said.

‘Absolutely shocking’

Lea lived with mother Judith and father David in Amsterdam. In June 1943 the family was deported to the transit camp in Westerbork and eventually Sobibor. She died aged 6.

Suzanna Flora Munnikendam is Lea’s second cousin – their grandmothers were sisters. She knew her grandmother died at Sobibor, but had never heard of Lea.

“It’s absolutely shocking,” she told CNN.

A spokeswoman from the Majdanek museum said the tags “grant an exceptional opportunity to identify” some of the victims.

She said: “The tangible evidence of their lives that were brutally ended upon their arrival at the Sobibor unloading ramp allow us not only to discover their history, but also to pass it on to the next generations and to keep the victims’ memory alive.”