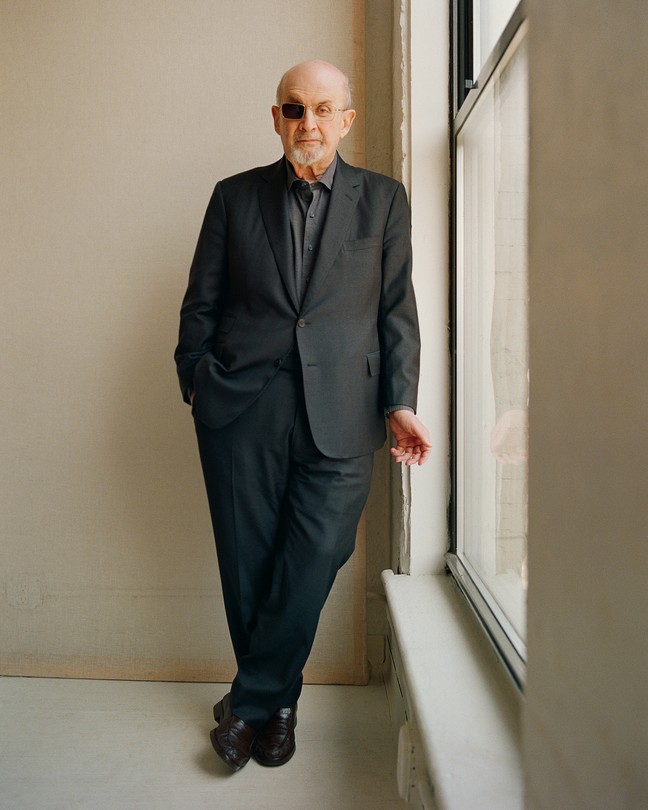

Salman Rushdie Strikes Back

In a new memoir, the author reckons with the attack that nearly took his life.

Salman Rushdie tells us that he wrote Knife, his account of his near-murder at the hands of a 24-year-old Shia Muslim man from New Jersey, for two reasons: because he had to deal with “the elephant-in-the-room” before he could return to writing about anything else, and to understand what the attack was about. The first reason suggests something admirable, even remarkable, in Rushdie’s character, a determination to persist as a novelist and a man in the face of terror. After The Satanic Verses brought down a death sentence from Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, which sent Rushdie into hiding, he kept writing novels and refused to be defined by the fatwa. When, decades later, on August 12, 2022, the sentence was nearly executed on a stage at the Chautauqua Institution, in upstate New York, where Rushdie was about to engage in a discussion of artistic freedom, he had to will himself through an agonizing recovery—pain, depression, disfigurement, physical and mental therapy, the awful recognition that the fatwa was not behind him after all. Then, to write this book, he had to stare hard, with one eye now gone, at the crime—even, in the end, to revisit the scene—because it stood in the way of the fiction writer’s tools, memory, and imagination.

“Something immense and non-fictional had happened to me,” Rushdie writes. Telling that story “would be my way of owning what had happened, taking charge of it, making it mine, refusing to be a mere victim. I would answer violence with art.” The most powerful manifestation of this art in Knife is Rushdie’s description—precise and without self-pity—of the price he pays for his words. The knife blows to his face, neck, chest, abdomen, and limbs are savage and very nearly kill him. He loses the sight in his right eye, which has to be sewn shut, and most of the use of his left hand. He is beset with nightmares and periods of profound gloom. The resilience he musters—aided by the love of his wife and family—is vulnerable, ornery, witty, self-centered, and heroic. It has made him a scarred symbol of free expression—or, as he acidly puts it, “a sort of virtuous liberty-loving Barbie doll.” He would rather be famous for his books, but he accepts his fate.

The other reason for writing Knife—to understand why he came within millimeters of losing his life—is more elusive. The “suspect,” Hadi Matar, committed the crime before about 1,000 witnesses and subsequently confessed in a jailhouse interview to the New York Post; still, he has pleaded not guilty. The trial hasn’t happened yet, and in fact has been postponed by this book’s publication—Matar’s attorney argued that Rushdie’s written account constitutes evidence that his client should be able to see. Matar’s story seems to be the all-too-familiar one of a thwarted loner on a glorious mission. He travels from New Jersey to Lebanon to see his estranged father and returns changed—withdrawn and angry at his mother for not raising him as a strict Muslim. He tries learning to box and watches videos in his mother’s basement, including a few of Rushdie’s lectures. He reads a couple of pages of The Satanic Verses and decides that the author is evil. He hears that Rushdie will be speaking at Chautauqua and stalks him there. Matar is a Lee Harvey Oswald for the age of religious terrorism and YouTube.

Rushdie isn’t much interested in him. He won’t name Matar, calling him only “the A.,” for assailant, ass, and a few other A words. Throughout the book, Rushdie expresses scorn for or indifference toward his attacker, calling him “simply irrelevant to me.” Still, he makes one sustained attempt to understand Matar: “I am obliged to consider the cast of mind of the man who was willing to murder me.” A journalist might have gone about the task by interviewing people who knew Matar and trying to reconstruct his life. Oddly, Rushdie doesn’t mention the names—perhaps because he never learned them—of the audience members who rushed the stage and stopped the attack, and he gives doctors in the trauma center impersonal titles such as “Dr. Staples” and “Dr. Eye.” Given that he dedicated the book to “the men and women who saved my life,” these omissions are striking and suggest a limit to Rushdie’s willingness to explore the trauma. After all, he’s a novelist, and his way of understanding is through imagination. He conjures a series of dialogues between himself and his attacker, but Rushdie’s questions—Socratic attempts to lead Matar to think more deeply about his hateful beliefs—elicit brief retorts, lengthier insults, or silence. Perhaps there really isn’t very much to say, and the conversation is inconclusive. It lasts as long as it does only because the man being questioned is trapped inside Rushdie’s mind.

The novelist might have gained more insight by imagining Matar as a character in a story, seeing the event from the attacker’s point of view, the way Don DeLillo writes of the Kennedy assassination from Oswald’s in Libra. But that would have given Matar far too much presence in Rushdie’s mind. His ability to survive as a writer and a human being depends on not forever being a man who was knifed, as he had earlier insisted on not being just a novelist under a death sentence. If Rushdie’s reasons for telling this story are to move on and to understand, this first reason is more important to him than the second and, in a way, precludes it.

Back in 1989, the fatwa hardly turned Rushdie into a hero. Plenty of Western politicians and writers, along with millions of Muslims around the world, put the blame on him for insensitivity if not apostasy. The knife attack was different—it drew nearly universal outrage and sympathy. Perhaps the horror of an attempted murder overcame any squeamishness about offending religious feelings. Perhaps the statute of limitations on blasphemy had run out, the fatwa too long ago to count. Perhaps there’s been too much violence since then in the name of a vengeful God and other ideologies. “This is bigger than just me,” Rushdie tells his wife in the trauma ward. “It’s about a larger subject.” The subject—the idea for which Rushdie nearly died—is the freedom to say what he wants. It’s under as much pressure today as ever—from fanatics of every type, governments, corporations, the right, the left, and the indifferent. Rushdie survived, but he has too many scars to be certain that the idea will. This book is his way of fighting back: “Language was my knife.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.