The Prince's Children

MAURO SENESI is a young Florentine journalist who was horn in Vollerra, Tuscany, thirty years ago. His first novel, I PIENI PETERI (”Emergency Powers”), was recently published in his native country. Here for the first time he turns to the short story form in English.

I SAID to him: no, let’s not go in. And he: OK, so it’s the prince’s garden, but what’s a prince? I’ve had enough of princes, here in Burma, too. In this world we’re all human beings with equal rights to the shade, he said, let’s jump over the wall.

No sooner said than done, he was already on top of that thick wall, and his hands were clinging to the broken glass cemented there on purpose to stop vagabonds like us from violating the gardens. You didn’t know it, he said, laughing, but my grandfather was a fakir.

If he cut himself, it’s true, just the same, that he didn’t seem to notice pain, or lose blood. Whereas I, when we were on the other side, was one great wound, and I think I even cried. No, I’m sure I cried, because he raised a finger to wipe a tear from my cheek and then looked at it scoffingly. So this is what you poor souls of the West know how to do, he said, cry.

And you Easterners, I asked him, what do you know how to do that’s so different?

Oh, you’ll see, Taianoko said. Instead of crying, we hate.

Who? I asked. Are there lots of people to hate?

The people who own gardens, he said, all the princes.

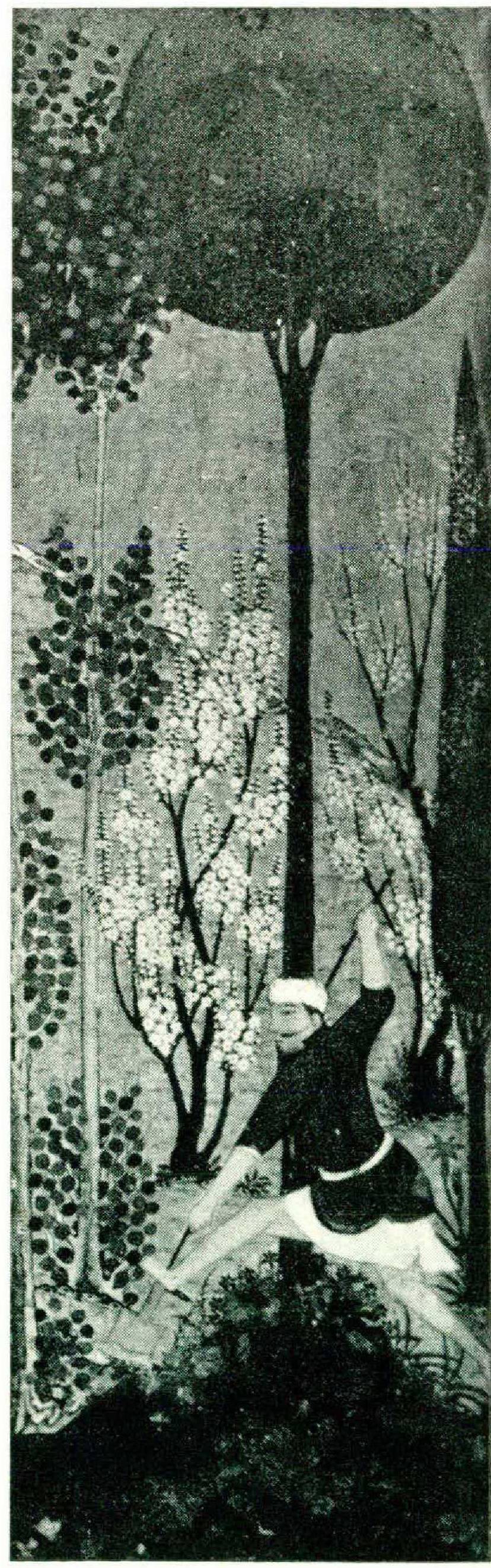

We were under the shade of great green trees, with tender grass beneath us, and the birds warbling all around, and right there, all of a sudden, the two children. They were motionless, so that at first I thought they were two statues, just as there are statues in rich people’s gardens.

She was a grown-up little girl, with her breasts already beginning to show and arched eyebrows fine, oh, so fine, above black and shining eyes. The boy’s head was cropped, large and round, then his face came down to a point, but his lips were fine and arched like the eyebrows of his sister. Both of them had slender, white, and fragile necks; necks so slender and white and fragile I had never seen before, in Burma or anywhere else.

Hey, exclaimed Taianoko, and who are you?

They didn’t answer, they only looked at him. As for me, it was as if they didn’t even see me. (But maybe this is the point, maybe I wasn’t there after all.) Taianoko stooped down low, until he was no taller than they were, and then began to make funny expressions with his mouth, with his eyes, with his nose; but no hint of a smile or of interest appeared on the face of either child; if anything, there was slight boredom.

So then Taianoko stood up and tried to hide his dismay, rubbing one huge red hand against the other. And talking to me: you see what princes and their children are like? There’s nothing that amuses them any more, not even if a poor tramp dusts the grass with his tongue.

And he did it, he stooped very low and with his tongue hanging out licked the grass all around the two children, who, ever motionless and distant, stood there watching without giving a single sign of appreciation, and I wanted so much to tell them: pet him or run away, as people do when dogs act like that. But do something, anything, don’t just stand there, without caring. I was a little scared, and somehow I pitied Taianoko. But I remained silent, because sure as certain the prince’s children couldn’t accept that sort of advice. And there was no petting they could do to him, nor chance of flight for them, nor right to pity for Taianoko.

They stood there proudly, only a short break in the rise and fall of the girl’s little breasts, while the boy’s large head swayed slightly on that neck of his, slender and erect as a flower stem when it resists the wind. In fact, the man now blew on their faces, hard, swelling his cheeks as if he wanted to uproot them, and they stood still, they didn’t even move their eyelids to blink.

I to him: what are you doing? They’re little kids, don’t you see? Let them alone. And he to me, out of breath: they’re princes. I: let’s take off, we still have a long way to go. He: it’s hot, there’s sun beating on the streets, and this is a fresh garden, with birds and tender children.

I had met him, Taianoko, outside the city. He was walking, and since I had to go on foot, too, we had come up together, but there was nothing else between us. Sure, I guess I had been amazed to listen to him talking for hours and hours under the sun, despite the dust which turned his tongue white, about the poor of the East and the closed gardens, about the wicked princes of the East.

He was a sanguine and cheery soul, good company. Sometimes he’d be nervous and noisy as if a whole exterminated mass, the poor of the East, were compressed inside of him, and sometimes instead, all of a sudden, he’d be closed and drooping and you could walk along beside him without even noticing he was there.

Why, he asked me, don’t they realize how important it is to be good to Taianoko, to be kind, so that Taianoko will forgive them and won’t hate them, won’t take this perfect chance to revenge himself?

It didn’t once occur to me to ask him why in the world the two children should have to win his forgiveness, nor why he should hate them, revenge himself. The incompatibility between him and them was so great, it was so natural and spontaneous as to have no need for reasons: it existed and that was it, like the raging wind and fragile flowers in the fields.

He blew on the children’s faces and they didn’t bat an eyelash, only the soft movement of hair brushing the girl’s rosy ears, only the swaying of the little prince’s head, only the chill within my heart. Taianoko stopped to swell his cheeks and then, again, suuuff, upon them with all his hot, dense breath. I felt it on me for a second and thought I’d be blown away.

The prince’s children always there motionless, not even taking each other’s hands for support and not telling me (if I was really there) to protect them or at least to try, not running away and not calling the soldiers, who without a doubt were flirting with the slaves in some quiet corner of that fresh garden.

Taianoko turned to me again: you see, stranger? I wanted to make them laugh, I wanted to make them run away, I wanted to teach them to forget they’re the children of a prince. Is it my fault, he said, if it’s impossible? Tell me yourself: is it my fault?

He had grasped them in that instant, had grasped their slender, erect, white necks with his hands, one on this side and one on that, neither the boy nor the girl had tried to work free; he had grasped them and now was squeezing his fingers, was raising them bit by bit from the ground, one on this side and one on that, almost gently.

Calmly, oh, so calmly! And yet it all happened so fast that I didn’t have time (if I was there, I repeat, but I hope not) to intervene, that the children didn’t have time to breathe even a feeble whimper. Gently, calmly Taianoko raised them, squeezing at their necks; then he laid them on the fresh green fragrant grass which was there in the prince’s garden.

Not even now had they closed their eyes; it was just the opposite, they were wide, wide open. But the girl’s little breasts were immobile and the boy’s large cropped head seemed the blossom of a cut flower. Taianoko’s hand trembled now.

He said: that’s what the poor of the East know how to do. He stopped the quivering of his hands, holding one over the other, and went on: you’ve got to do it, with princes, if you want to feel the freshness of garden air. He lay down beside the two dead children, on the soft grass, spreading his arms and letting his eyes close, so as to show what perfect bliss was his: only a vein, twisted, black, and turgid, like a tiny snake, throbbed in his throat.

And me just standing there, while soldiers came running from all directions and women wrapped in blue, red, and yellow veils came running too, and each of them tried to cradle one of the children, then would almost drop the little body back down on the ground. Finally there was a man dressed in gold, with a huge turban and, right in the middle, an enormous, sparkling ruby. To ask who, who had killed them.

I pointed to Taianoko and he admitted it, with a simple nod of his head. Slowly he raised himself from the ground to come face to face with the prince, even though the soldiers were hanging to his arms trying in vain to keep him down.

Why, asked the prince, did you do it? What reason could you possibly have had, distractedly sorrowful he asked, to kill the gardener’s children?