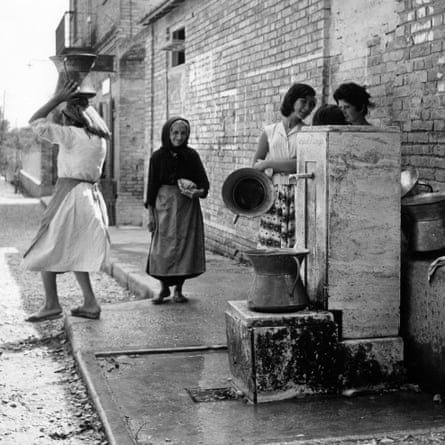

In 1941 Cesare Pavese wrote a postcard to the 25-year-old Natalia Ginzburg in the Abruzzi, where she was waiting out the war with her three children: “Dear Natalia, stop having children and write a book that is better than mine.” The result was The Road to the City, published in 1942 under a pseudonym because her husband, Leone Ginzburg (a colleague of Pavese’s at the Einaudi publishing house), was in trouble for his antifascist activities. Thus began a 50-year writing career. Ginzburg was influenced by Pavese and was later happy to describe herself as a neorealist, part of a literary movement that echoed contemporary Italian cinema. She looked back on neorealism as “a way of getting close to life, of getting inside life, inside reality”. But her voice was distinctive from the start: cold in its exposure of false sentiment while warmly attentive to the details of family life and female experience.

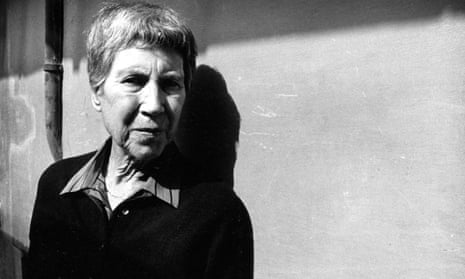

Ginzburg has long been famous in Italy as a writer, publisher (she worked alongside Pavese and Italo Calvino at Einaudi after the war) and politician (in 1983 she was elected as an independent to the Italian parliament, where she gave speeches about sexual violence, disarmament and the destruction of rural life). However, she was considerably less read in Britain than the male neorealists until last year, when Daunt reissued her 1962 essay collection The Little Virtues and her 1963 novel Family Lexicon. Now they are reissuing her 1961 novel Voices in the Evening.

Reading these books, I don’t think I’m alone in feeling a swift readerly intimacy. In this respect, it’s a bit like reading Elena Ferrante, but where reading Ferrante can seem like making a new friend, reading Ginzburg is more like finding a mentor. Here is someone who shares the experiences of daily life but also brings a fully formed moral and intellectual compass that allows you to see these experiences more objectively. From the smallest components of domestic life, she builds a world with the ethical complexity of the great 19th-century novels.

The essays in The Little Virtues lead back to the second world war and its aftermath, providing an anatomy of these years, with their worn shoes, food shortages and existential depletion. In the story Winter in the Abruzzi, she evokes life in their wartime village and then abruptly describes her husband’s death in prison in 1943. Did this really happen to them, she asks, “who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow”?The reckoning with war’s assault on the ordinary continues in The Son of Man, written in 1946. “There has been a war and people have seen so many houses reduced to rubble that they no longer feel safe in their own homes, which once seemed so quiet and secure.”

The collection ends with two masterpieces that push out into a larger moral landscape. The first, Human Relationships leads movingly through the stages of life from childhood to adulthood. Ginzburg writes, unusually but absolutely assuredly, in the first person plural, recounting “our” rebellion against our parents, our search for the right friend and the right lover, moving onwards into motherhood and war. The whole of life is here, but perfectly scaled down to focus on the everyday, with its slammed doors and exercise books (best friends briefly with a popular girl, she examines her precious book with its “beautiful angular handwriting in blue ink”). Along the way, she asks fundamental questions about how we can be moral beings who love our children, our friends and neighbours and at the same time serve a higher purpose (at once God and a communist vision of the collective). The shock of motherhood, then as now, is in its selfishness: “We love our children in such a painful, frightening way that it seems to us we have never had any other neighbour … Where is God now? We only remember to talk to God when our baby is ill.” This is changed by war, when she learns to ask for help from passersby. For a while, she renounces possession of things and people, growing up in the process. “We are adult because we have behind us the silent presence of the dead, whom we ask to judge our current actions and from whom we ask forgiveness for past offences.”

The final essay, The Little Virtues, suggests what we should teach our children: “I think they should be taught not the little virtues but the great ones. Not thrift but generosity and an indifference to money: not caution but courage and a contempt for danger; not shrewdness but frankness and a love of truth; not tact but love for one’s neighbour and self-denial; not a desire for success but a desire to be and to know.” In other hands, advice like this could be unappealingly didactic, but here it feels the result of patiently learnt experience. These values thread through Family Lexicon, Ginzburg’s first commercial success, published when she was 47. This is the world of Ginzburg’s early life in Turin, with her Jewish biologist father and her Catholic, music-loving mother, the whole family arguing about politics. The book’s title refers to the phrases that characterise each person, phrases that become “our Latin, the dictionary of our past”, once war destroys their world.

Along the way, Ginzburg addresses questions of literature and politics. Calvino, in Hermit in Paris, writes that the “climate of poverty and feverish undertakings” of the postwar years inspired his generation of leftists foremost with “a desire for action”. Ginzburg describes the excitement of the fever, “when everyone believed himself to be a poet and a politician” and was finding that “many words were in circulation and reality appeared to be at everyone’s fingertips”. She then shows it becoming more debilitatingly sickly: “The common error was to still believe that everything could be transformed into poetry and words. This resulted in a loathing for poetry and for words … in the end everyone kept quiet, paralysed by boredom and nausea. It was necessary for writers to go back and choose their words, scrutinise them to see if they were false or real, if they had actual origins in our experience.”

This is the quest that characterises neorealism, with its dual commitment to actual experience and to reinventing that experience in new artistic forms to make it count as real again. In compiling a family lexicon, Ginzburg finds her own way to do this: fastening on the words that have brought not just her family but the whole community into being. She is asking if she can use them to stake her claim on reality and if there can be a form of community after fascism that is authentic and free of lies. She is doing this, explicitly, as a woman. In her 1949 essay My Vocation, she described her early attempts to write like a man, using “irony and nastiness”, and her realisation after having children that she could only write authentically as a woman: “I no longer wanted to write like a man, because I had had children and I thought I knew a great many things about tomato sauce, and even if I didn’t put them into my story it helped my vocation that I knew them.”This is one of the places where I find Ginzburg so stimulating as a mentor from the past. She’s offering women writers our daily experience not as domestic writing but as an ingredient in the larger project of writing about complicated times.

Voices in the Evening, published two years before Family Lexicon, is in some ways a paired book, where she’s engaged in the same quest to find words that have “actual origins in our experience”. She had been living in England and reading Ivy Compton-Burnett when she wrote it, and Compton-Burnett’s style infuses the pages of polyphonic dialogue. I find this earlier novel more satisfactory as an act of storytelling than Family Lexicon, where the narrator occludes her own experience. In her introduction to The Little Virtues, Rachel Cusk praises Ginzburg in Family Lexicon for separating “the concept of storytelling from the concept of self and in doing so [taking] a great stride towards a more truthful representation of reality”. Cusk finds in Ginzburg’s narrator a prototype for her own recent trilogy. Certainly Ginzburg is making a point about the futility of insisting on selfhood, and this is partly a political point, made by someone who remained a communist even after she broke with the party. But Ginzburg’s narrator is implicated in the lives of her characters in a way that Cusk’s is not, and so it can feel misleading that she holds back so much about her life. She marries and moves city, but tells us only as an afterthought.

In Voices in the Evening, the misleadingness itself is probed for its significance. The first half of the book recounts in minute detail the histories of the father and children of the De Francisci family, owners of the factory whose acrid smell permeates the whole town. These characters, like those in Family Lexicon, are deftly drawn with a few telling characteristics (one son explains everything by psychoanalysis, a daughter-in-law powders her face so much that she looks dusty). Though we understand that this is a world where no one story can be told without reference to the rest of the community, we might wonder why the narrator, Elsa, is regaling us with these tales. Then, halfway through, we learn that she’s had an unsatisfactory love affair with Tommasino, one of the sons.

After this, the novel becomes more tightly focused on the quiet build up and deflation of Elsa and Tommasino’s relationship. Secret, strangely precious afternoons of love-making and talking at a flat in town give way to a formal engagement that kills their love, making Tommasino feel that he has turned his back on his own soul. It’s through this relationship that the boredom and nausea of the postwar world is revealed most painfully, allowing Ginzburg to portray a wasted generation and by the casual brutality that remains in the wake of war left crippled by its past.

Near the end, Tommasino tells Elsa that he can’t assert himself because he feels that “they have already lived enough, those others before me; that they have already consumed all the reserves, all the vitality that there was for us.” This takes us back to the dilemmas described in Human Relationships and forwards to those in Family Lexicon. They are dilemmas faced also by Calvino and Pavese (whose suicide haunted Ginzburg as it haunted Calvino) and confronting us in only subtly mutated forms today. How to keep the energy and excitement of the postwar world generative rather than merely intoxicating; how to build a new world with integrity; how to live as an individual authentically within a community; how to survive the judgment of the silent dead.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion