Founded in 1887 by a Finnish sea captain named Gustave Niebaum, Inglenook is a sprawling 1,680-acre winery known as “the Queen of the Napa Valley”. The estate contains 280 acres of vineyards, a Queen Anne-style Victorian mansion and a magnificent stone-and-iron chateau, all of which combine to create a refined northern Californian ambience that is about as far away as it’s possible to imagine from being in the shit in Vietnam.

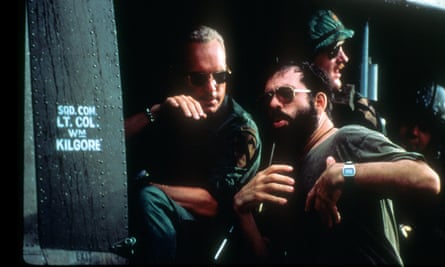

Yet arguably the greatest war film of them all owes much to Inglenook. Bought in 1975 by Francis Ford Coppola, using his spoils from The Godfather, he promptly risked the property, staking it to raise money for what would become one of the most arduous and challenging productions in the history of film. It is also here, in the estate’s old carriage house, that Coppola has spent the past two years restoring and refining a new – and he says definitive – version of that film: Apocalypse Now: Final Cut.

When he welcomes me to Inglenook, Coppola, who turned 80 in April, is almost unrecognisable from his 70s heyday. Gone are the hirsute beard and thick-rimmed spectacles that were once his trademark; they are replaced by neat white stubble and, slung loosely around his neck, a modern pair of magnetic glasses that unclip at the nose. He has also dropped four and a half stone (64lb), the result of four months spent at a weight-loss clinic. In conversation he tends towards the philosophical, and his elliptical answers stray from his films towards his admiration for the likes of Aristotle and William Morris. He is well aware that he’s doing this, of course, but, as he observes with a smile: “When you’re 80, you don’t have to talk about anything you don’t want to talk about.”

It is 40 years this month since Apocalypse Now first hit cinemas, and to mark the anniversary Coppola returned once again to his editing suite. In a nutshell, his assessment was that he had made too many concessions in the film’s original 1979 release, and that the march of time had blunted some of its surreal edge. “What is considered avant garde in one moment, 20 years later is used for wallpaper and becomes part of the culture. It seemed that’s what had happened with Apocalypse,” he says.

In contrast, however, he feels he somewhat overegged the 2001 redux version, which added 49 minutes to the original’s running time of two hours and 33 minutes. He has now cut back about 14 minutes to finally arrive at his ideal, which he argues is the strongest elucidation yet of the film’s examination of human morality. “I really feel that this version of Apocalypse Now achieves more of what that theme has to give than any of the previous versions,” he says.

The film transposes Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness on to the conflict in Vietnam, and Coppola rewrote and reworked John Milius’s original script so that it would be more faithful to the book. “You have to realise, when I was making this I didn’t carry a script around,” he says. “I carried a green Penguin paperback copy of Heart of Darkness with all my underlining in it. I made the movie from that.”

The result is a savage and darkly comic examination of the absurdity and double standards of war. Early in the film, Robert Duvall’s Lt Col Kilgore – who is in the midst of a helicopter attack against an innocent village, and will soon order a napalm strike – witnesses a Vietnamese woman toss a grenade into one of his choppers. “Savages,” he spits. Later on, Marlon Brando’s Col Kurtz observes: “We train young men to drop fire on people, but their commanders won’t allow them to write ‘fuck’ on their airplanes because it’s obscene.”

It is to my surprise, then, that Coppola hesitates to call the film “anti-war”. “No one wants to make a pro-war film, everyone wants to make an anti-war film,” he says. “But an anti-war film, I always thought, should be like [Kon Ichikawa’s 1956 post-second world war drama] The Burmese Harp – something filled with love and peace and tranquillity and happiness. It shouldn’t have sequences of violence that inspire a lust for violence. Apocalypse Now has stirring scenes of helicopters attacking innocent people. That’s not anti-war.”

He pitches his own alternative, by way of counter example: “I always thought the perfect anti-war film would be a story in Iraq about a family who were going to have their daughter be married, and different relatives were going to come to the wedding. The people manage to come, maybe there’d be some dangers, but no one would get blown up, nobody would get hurt. They would dance at the wedding. That would be an anti-war film. An anti-war film cannot glorify war, and Apocalypse Now arguably does. Certain sequences have been used to rev up people to be warlike.”

I ask him if he feels any guilt. “No,” he says. “I don’t feel guilty, because I know my role in the whole process.”

Apocalypse Now’s ill-starred 238 days shooting in the Philippines have become the stuff of film-making legend, much of it captured in Hearts of Darkness, George Hickenlooper’s documentary about the making of the film pieced together from behind-the-scenes footage shot by Coppola’s wife Eleanor. The movie’s travails were legion. Coppola dropped his leading man, Harvey Keitel, a couple of weeks into shooting, only for his replacement, Martin Sheen, to have a near-fatal heart attack. A typhoon destroyed much of the set. Coppola had an epileptic seizure. The helicopters he had rented from the Philippine government repeatedly disappeared off to go to take part in actual combat, fighting an insurgency in the south of the country. The pilots were rarely the same from rehearsal to rehearsal and the choppers had to be repainted twice a day to change their colours from American back to Filipino. When Brando turned up on set he was overweight and underprepared. He insisted his character should be called Col Leighley, and Harrison Ford shot scenes referring to him by that name which had to be redubbed later on when Brando belatedly came around to the name Kurtz.

None of this was helped by reportedly prodigious drug use among the film’s cast and crew, with Dennis Hopper apparently asking for “about an ounce of cocaine” in exchange for taking on his role. Coppola, however, says he personally steered clear of that kind of debauchery. “I never took drugs at all in my life, except for some grass,” he says. “I found that the effect that grass would have on me was interesting because it made me extremely focused. Also, if I smoked a joint I couldn’t fall asleep. I would want to work, and then I would stay up all night to rewrite the script. I’ve had cocaine but I found it very unpleasant. It’s too much. In terms of Dennis Hopper, God knows what he was doing.”

No matter how often the production lurched from one crisis to another, Coppola consistently resisted the temptation to release a film that didn’t meet his own exacting standards. “That definitely is not Francis’s MO,” says Walter Murch, the Oscar-winning sound designer who also edited much of the film. “There are people under those circumstances, when something is going badly, who try to retreat to a safe place. This only encouraged Francis to go even further. Always, when presented with the option of A or B, if B was riskier yet offered the potential for something really unique, he would go for that. It was breathtaking at times, both in production and post-production.”

It is highly doubtful that any major production would be allowed to take such risks today. Coppola argues that, as well as the technological advances that have transformed movie-making since the 70s, power has tilted in the direction of studios and away from directors. “There’s not only control with the extraordinary things you can do in … it shouldn’t even be called post-production. It is all production,” he says. “But, also, the studios during the period of the 70s learned how to prevent runaway directors. I mean the famous experience with United Artists and Michael Cimino’s film Heaven’s Gate so traumatised companies that they developed techniques to prevent that type of runaway-director behaviour which we, in my generation, sort of exploited.” The perfectionist Cimino’s slow-moving, hugely expensive and enormously long western flopped so badly it bankrupted the studio.

At the end of Hearts of Darkness, Coppola states his belief that: “One day, some little fat girl in Ohio is gonna be the new Mozart and make a beautiful film with her little father’s camcorder, and for once the so-called professionalism about movies will be destroyed for ever and it will become an art form.” Now that most of the population carries a digital video camera about their person at all times, I ask if Coppola still believes the proliferation of cheaper video equipment will transform Hollywood.

“The story of Hollywood has to do with who owns it,” he says. “In the old days, it was owned by these characters like Sam Goldwyn, Darryl Zanuck and Jack Warner, who were just as vulgar and abusive as Harvey Weinstein. Maybe not Sam Goldwyn and a few others. I don’t pardon it, it was terrible how they were, but the difference was that the owners loved movies. Today, the owners of the film business are very many steps removed. They’re pretty much telecom companies who borrowed an enormous amount of money to be able to buy Universal or CBS, so all they care about is servicing their loan.

“Where the little girl from Ohio is relevant is that now we have this double film industry,” he continues. “We have the studio pictures, which we know are really the same movie over and over and over again, and then there’s this very fertile independent film business, which are all the kids I was referring to. That’s the cinema. The cinema is not the industrial cinema. The cinema is independent cinema. Even this second golden age of television comes from people who wanted to make films like we did in the 70s but weren’t permitted to, so they did it for television. We’re in a blossoming of cinema art, I feel. It’s just that they do it with their parent’s credit cards.”

The fact that Apocalypse Now retains its power to shock and awe four decades on is testament to Coppola’s determination to do it his way. That meant risking everything, but today he can look out over Inglenook and know he rolled the dice and won. “I never let not knowing how to do something stop me from trying to do it,” he says. “I always got myself into those situations because it was exciting and I got to do all these wonderful, nutty things. Is the point of life just to live some normal, calm, moderately happy existence? I mean, you only get it once.”