When Being John Malkovich opened in 1999, nobody knew the name of its screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman, who’d spent the previous 15 years laboring in the comedy salt mines, submitting articles on spec to National Lampoon, writing a number of unproduced pilots, and landing gigs on short-lived (if beloved) sketch shows like Get a Life and The Dana Carvey Show. Yet as soon as it premiered – and for every project he did afterwards – it was talked about as a Charlie Kaufman film, even though it was directed by Spike Jonze, whose work on innovative commercials and videos for Weezer (Buddy Holly), Beastie Boys (Sabotage), and others had earned him a reputation as one of the most sought-after talents in the business. This was virtually unprecedented; even Robert Towne, whose script for Chinatown is frequently cited among the best ever written, wasn’t credited over its director, Roman Polanski.

Still, it was only natural to cite Kaufman for the inspired absurdity of his premise, which treats the very specific consciousness of an esteemed character actor as the site for a grown-up Alice in Wonderland, a place where people can escape their sad, desperate lives for 15 minutes before getting thrown out on to a ditch by the New Jersey Turnpike. It was Kaufman who imagined The Belle of Amherst performed by a 60ft tall Emily Dickinson puppet (“gimmicky bastard”), a workplace conceived for the short-statured on the 7½th floor of a nondescript office building (“The overhead is low!”), and 44-year-old humans as vessels for those who want to live forever. And none of that even accounts for the random one-liners and conceits that are jammed into the screenplay, or the emotional richness of its themes, from loneliness to self-loathing to yearning, and how love can transcend bodies and genders.

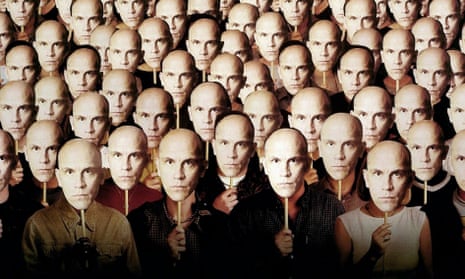

The best of Kaufman’s work after Being John Malkovich has clarified his approach to storytelling. Through various high-concept, off-the-wall conceits – a screenwriter named “Charlie Kaufman” struggling to adapt The Orchid Thief (Adaptation), a surgery that erases memories of a failed relationship (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), a theater production that metastasizes like a cancer (Synecdoche, New York), a stop-motion world where everyone is the same (Anomalisa) – he balances absurdist comedy with insight into specific human vulnerabilities. These enormous and crazily ornate apparatuses are constructed around sentiments that are touchingly precious, like the value of holding on to even painful memories or, in this case, the lengths we’ll go to make ourselves appealing to those we desire.

The film also introduces the Charlie Kaufman type: pasty and disheveled, with bad hair and lumpen bodies and a thin film of flopsweat on the face. He’s not a hero, either, which is another great and rare quality Kaufman has as a screenwriter. He doesn’t want his characters to be loved; he’ll settle for them being identifiable and understood. To that end, Craig Schwartz (John Cusack) is a self-involved artiste, obsessed with getting some recognition for his uncompromising work as a realist puppeteer, but mostly languishing in a cramped, lightless garden apartment with his wife Lotte (a frizzy-haired Cameron Diaz) and her pet parrot and chimpanzee. Soon after his nimble fingers land him a job as a file clerk at LesterCorp, a company on the 7½th floor of the Mertin-Flemmer Building in New York, he falls hard for the glamorous Maxine (Catherine Keener), who wants nothing to do with him.

When Craig discovers a hidden portal that leads into the mind of John Malkovich, new possibilities open up for everyone except the hilariously tormented actor, who’s subject to constant insults and the eventual forfeiture of his body. It’s important to note that Maxine never goes into the portal herself – she’s just happy to run an after-hours business called JM Inc and collect her half of the $200 people will pay for their 15 minutes – but Craig and Lotte use Malkovich as a separate means to pursue their attraction to her. Lotte experiences some form of transexual awakening, thrilled that she’s finally discovered her true self in seeing Maxine through his body. (“Don’t stand in the way of my actualization as a man!”) Craig, for his part, can manipulate the actor like one of his puppets and be someone that Maxine will accept as a partner.

Being John Malkovich is a dense piece of work, as if Kaufman needed his own Malkovichian vessel to serve as a clearing house for ideas that built up over 15 years in the screenwriting wilderness. (Kaufman’s awareness of these tendencies is exposed in Synecdoche, New York.) But one of the pleasures of the film is how multiple viewings bring out different aspects of it: I’ve never heard a group of critics laugh harder than its first screening in Chicago 20 years ago, with a then-full-voiced Roger Ebert bellowing from the back row. It’s perhaps later that something like Lotte’s longing becomes so powerful, or that you lock into the idea of the body and mind as prisons of thwarted desire, or you appreciate Jonze’s directorial touches and his commitment to a modest, grimy aesthetic. On this viewing, it was Malkovich’s own journey that stood out to me, from the various slights directed at him (everyone remembering him from “that jewel thief movie”, Craig muzzling him as “an overrated sack of shit”) to his wonderful comic apoplexy to the particular level of celebrity that would have made him nearly irreplaceable by another star. (“What is this strange power Malkovich exudes?”)

One more 1999 connection stands out: in a deliberately mundane point-of-view sequence in his apartment, Malkovich is ordering periwinkle towels over the phone, recalling the “cornflower blue” that Edward Norton’s narrator singles out in Fight Club from the same year. In both films, there’s something in the air about the meaningless of material things – even American Beauty, which criminally defeated Being John Malkovich for original screenplay that year, had Kevin Spacey yelling about a couch being “just a couch” – and a common longing for a more meaningful life. Norton finds it in violence and machismo while Kaufman’s characters can only find themselves by discarding their old lives, as if Malkovich was the pupa stage in a metamorphosis. For them, being John Malkovich for 15 minutes is better than a lifetime of being themselves.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion