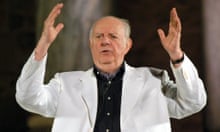

The dramatist, director, actor, painter and political provocateur Dario Fo has died aged 90. When Fo was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1997, the Swedish committee praised his achievement in reviving the traditions of the giullari – the jester-cum-minstrels of the middle ages who improvised their comedy, jibing at the establishment of the times. His greatest achievement as an actor-author was Mistero Buffo (1969), a reworking of medieval mystery plays, which he performed with masterly skill as a one-man show, making exhilarating use of an onomatopoeic language called grammelot and a mixture of dialects. Other actors have since done their best to emulate him, with varying degrees of success, and his texts will continue to inspire lively theatrical invention.

Fo was born in San Giano, in Lombardy, northern Italy, son of Pina (nee Rota) and Felice. His socialist father was the stationmaster of this small village named after an obscure saint, where trains between Milan and the Swiss borders rarely stopped. Felice was transferred to other stations, including the fishing village of Porto Valtravaglia, where the young Dario heard the locals singing and recounting tales, giving him his first lessons in the art of performance. Pina later published a book of family reminiscences.

At 17, Fo volunteered for Mussolini’s fascist republic army after the armistice of 1943. He said his intention was to protect his father from reprisals, but when he realised that he was getting too involved in military action, he deserted and joined the partisans.

Fo decided to study art in Milan, although once there he turned to architecture. After a nervous breakdown, he was advised by a doctor to pursue a career he felt certain he would enjoy. This brought him into the theatre, where he discovered Eduardo De Filippo, who was making comedy out of the real-life drama of Italy’s postwar years. He learned stagecraft from watching the work of directors such as Giorgio Strehler, and studied Antonio Gramsci, Bertolt Brecht and Vladimir Mayakovsky.

After early success with his own radio programme, Fo collaborated on a satirical revue, Il Dito nell’Occhio (Finger in the Eye), for which the mime Jacques Lecoq coached him, teaching him in particular how to make good use of his gangling arms and legs. A second, more political, musical revue ran into trouble with the censors.

In 1954 Fo married Franca Rame, a showgirl from a Milanese theatrical family, and their son, Jacopo, was born a year later. They co-starred in the film Lo Svitato (The Screwball, 1956), which Fo co-wrote, and in 1958 formed their first theatrical company together. Fo had commercial success with a series of original plays full of ingenious invention. The best was perhaps Isabella, Tre Caravelle e un Cacciaballe (Isabella, Three Sailing Ships and a Con Man, 1963), about a Spanish actor condemned by the inquisition who, at the gallows, performs a play about Christopher Columbus’s expedition. Rame portrayed Queen Isabella and Fo was in sublime form as both the actor and Columbus. Using the simplest of stage effects, he made this one of his most eye-boggling productions.

For a decade, Fo and Rame performed a new show each season, touring throughout Italy. There was always political controversy surrounding his satires but his biggest clash with the censors came when he and Rame were signed up by the broadcaster RAI in 1962 for a major show. RAI officials were soon frightened by some of Fo’s satirical sketches, based around the everyday lives of working-class people, and wanted to make cuts. After weeks of battling, Fo and Rame stormed out. They were not seen again on Italian television for 15 years.

Their work became more and more pungent but no less popular. After their last mainstream show, La Signora è da Buttare (The Lady is for Throwing Out, 1967), the time came for them to stop depending on the convenience of bourgeois theatre. They formed an independent co-operative, Associazione Nuova Scena, but by 1969 had left that to set up their own group, La Comune, based at first in a backstreet hall in Milan. In 1974 they occupied an abandoned pavilion in a public garden, the Palazzina Liberty. It was here that La Comune took an active role in the political and cultural life of Milan in the 1970s.

Throughout that decade, Fo’s international reputation grew. His early plays had already been translated into many languages but there was great interest in the plays of this new period, including Morte Accidentale di un Anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist, 1970), inspired by the mysterious death of Giuseppe Pinelli in a police station after a bomb attack in Milan a year earlier.

Non Si Paga, Non Si Paga! (Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay!, 1974) starred Rame as a housewife looting a supermarket to protest against the economic crisis. Such works were farces that played to packed audiences in Italy and around the world, including London, where Fo and Rame had several successes in the 1980s, notably at the Riverside Studios.

It was with Mistero Buffo that Fo’s creative progress touched the heights of genius. These stories and parables, including the resurrection of Lazarus and the marriage at Cana, were powered by Fo’s mimicry and linked together by his erudite patter, which left audiences in fits of laughter as he drew parallels between the past and the present. His grotesque interpretation of religious situations, imaginary and real, was considered blasphemous only by the most bigoted of spectators. When Fo and Rame were finally reinstated by Italian television in the late 1970s, and his filmed live performance of Mistero Buffo was transmitted, there was an inevitable outcry from the Vatican.

For Fo, the church was like a theatre. In 1984, when I was the associate producer of a BBC Arena film about his work, we drove with him to Cesenatico on the Adriatic coast, where he had a modest summer home. En route, Fo suddenly stopped the car and led us into a medieval church, where we filmed him singing a Gregorian chant and explaining to us that churches were built for performance.

Fo loved to direct opera. His imaginative 1978 staging at La Scala of Stravinsky’s Histoire du Soldat, with a strong Marxist slant, counts among his most brilliant productions. His reworking of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera in the early 80s was not as well received, although when Fo took over the role of Peachum it won more favour. Rossini was his favourite composer, and his Italiana in Algeri at the Pesaro festival in 1994 was a triumph. In his 2003 production of Rossini’s Il Viaggio a Reims at the Finnish National Opera in Helsinki, he hinted at parallels with contemporary rulers in his send-up of Charles X’s coronation.

While Fo was directing The Barber of Seville in Amsterdam in 1987, Rame appeared on a popular Italian TV show to announce that she and he were separating. However, the marriage was soon patched up. Rame had been at Fo’s side in all his political and artistic battles and, when necessary, accepted a secondary role as part of the creative team, though she also wrote her own plays. Her vigorous political stands as a militant leftist were often stronger than Fo’s good-humoured, soapbox-style protests. Receiving his Nobel prize, Fo said that he shared the credit with Rame, as she had been his muse. Even as they subsequently suffered from failing health, they always rediscovered the vigour and inspiration to continue creative work.

Fo continued to enjoy writing plays that jibed at Italian political scandals. In the late 90s, Il Diavolo con le Zinne (The Devil With Boobs) transposed the Tangentopoli (Bribesville) scandal to 16th-century Florence. The corrupt magistrate was played by the Italian stage’s leading traditional actor, Giorgio Albertazzi, who had never hidden his rightwing sympathies. Their collaboration surprised many but they declared they were both anarchists in their own ways. They later made a TV documentary series on the history of the theatre.

Among his next plays, the most controversial was L’Anomalo Bicefalo (The Abnormal Two-Brainer, 2003), a hilarious if cruel satire on Silvio Berlusconi, who is seen recovering his identity after an assassination attempt against him, and Vladimir Putin. The Russian is killed but the Italian is saved after the remains of Putin’s brain are grafted on to his.

Fo then wrote a monologue entitled Peace Mom (2005), dedicated to Cindy Sheehan’s protest after her soldier son was killed in Iraq. It was staged in London with Frances de la Tour. Rame later performed it in a revival of Mistero Buffo at the Verona Arena in 2006.

Fo’s many publications included several lively but erudite manuals on theatre. With Rame’s help, he published a deluxe volume dedicated to Aurelius Ambrosius, the patron saint of Milan. It was in the basilica of Saint Ambrosius in Milan that they had married. Fo’s most impressive literary work was a novelised slice of autobiography about his childhood and adolescence, Il Paese dei Mezaràt (The Land of Half-Rats, 2002). In one section, he described his first visit as a boy to Milan, where he discovered the great painters.

He returned to art for his most illuminating work in his twilight years. As well as exhibiting his own paintings, he won praise for one-man shows, held in public squares or auditoriums and dedicated to the artists he adored. Fo’s own drawings of the works he discussed were projected alongside these lecture-performances, which were broadcast on Italian TV. In Modena he performed in front of the Romanesque cathedral, which has astonishingly theatrical statues and friezes; Fo brought them to life brilliantly, just as he had done with the biblical parables of his Mistero Buffo.

After Rame’s death in 2013, Fo decided the best way to commemorate her was to continue the work they had done together. Still the satirical anarchist, Fo gave public support to the comedian turned politician Beppe Grillo, and later found a new kindred anarchistic spirit in Pope Francis, whom he celebrated with a mock-medieval play about St Francis of Assisi. He astonished even his admirers with his first novel, La Figlia del Papa (The Pope’s Daughter, 2014), in which he recounted his interpretation of the life of Lucrezia Borgia, seeing her as a forerunner of female protesters against corruption in our own time.

Fo is survived by Jacopo.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion