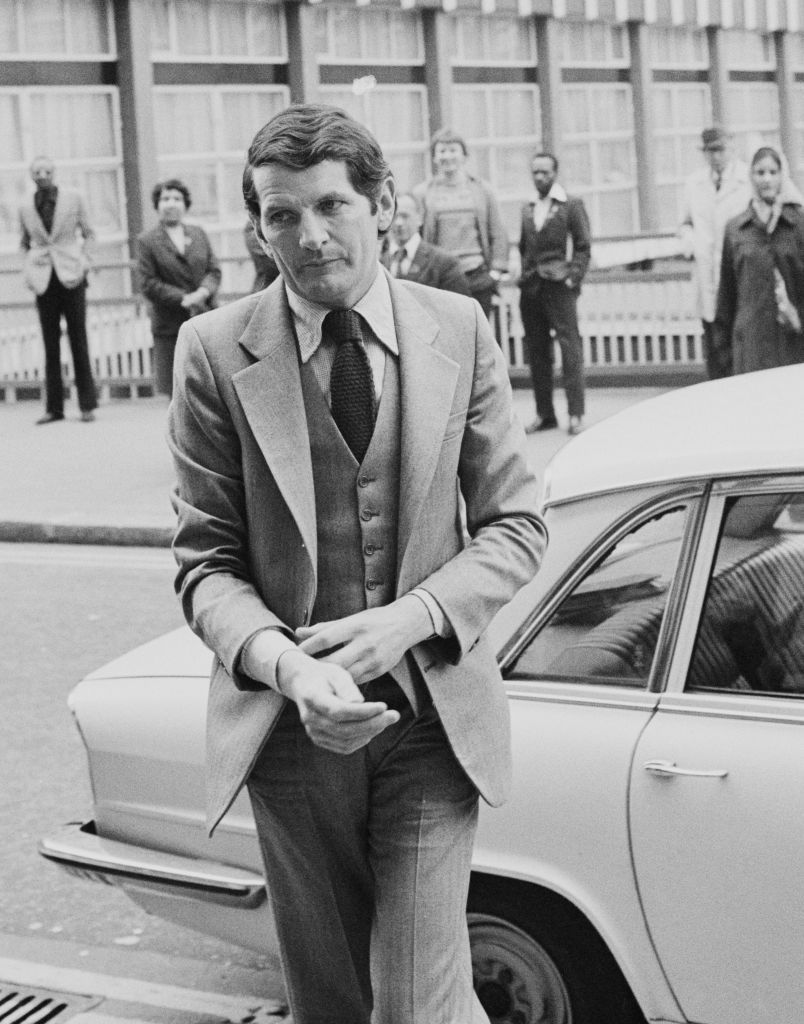

- Hugh Grant stars in a new Amazon miniseries about Jeremy Thorpe, a British Liberal Party politician accused of murdering his lover Norman Scott.

- The show has been nominated for three Golden Globes.

- Thorpe, a married father of one, went to great lengths to hide his many relationships with men for fear that it would ruin his political career.

- In 1978, he was arrested on charges that he conspired to have Scott shot by a bumbling hitman named Andrew Newton.

If you're anything like me, then your first thought upon hearing that Hugh Grant was starring in 70s-era miniseries called A Very English Scandal was "oh, that must be about the Profumo Affair. I hope I can remember what that is."

Good news: Any fogginess on the details of the Profumo Affair won't hold you back here. But chances are if you're American you aren't familiar with the details of this particular British scandal either.

Grant plays Jeremy Thorpe, a politician who was accused of taking out a hit on his former lover, Norman Scott, played by Ben Whishaw. (Both Grant and Whishaw are nominated for Golden Globes—for Best Actor and Supporting Actor respectively. The series is also nominated for Best Limited Series or TV Movie.)

Though the titular scandal may be singular but the story's many layers of controversy punctured the insularity of mid-century Britain: The shocking fact of a politician accused of a monstrous act; the illicit relationship between two men at a time of widespread homophobia; and the power and class disparity between Thorpe, a wealthy politician, and Scott, a stable hand.

Watch the trailer:

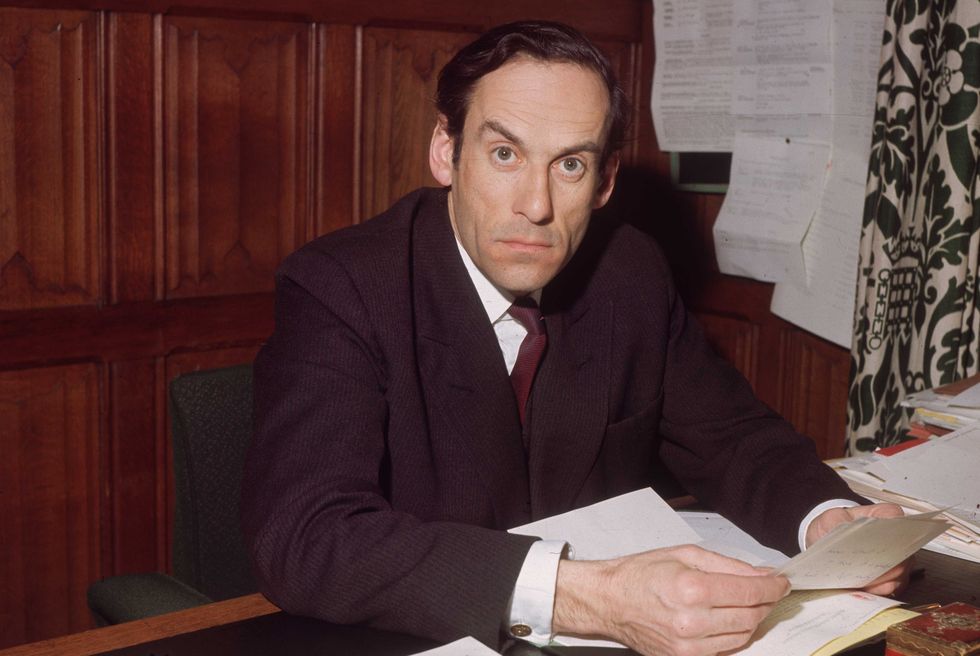

Who Was Jeremy Thorpe?

Thorpe was a 20-year member of the British Parliament. He was born in 1929 to a well-connected family in Surrey—both his father and grandfather were Tory MPs. He went to Eton and Oxford, where he apparently had his first brush with scandal. "A faint whiff of sulphur, connected with ballot-rigging, clouded even his election to the presidency of the Oxford Union as long ago as 1951," reads his 2014 obituary in the Guardian.

Thorpe was elected to Parliament as a Liberal candidate in 1959, narrowly defeating both the conservative MP. Despite his posh upbringing, he has "a radical cast of mind," as the Guardian put it. "He was, he insisted, deeply opposed to privilege and used to talk about his shock at seeing his mother call up a servant from the basement of their house to take a few lumps of coal from the scuttle to put on the fire."

He was known for his flair on the campaign trail, his talent for mimicry, his love of a good party, and his personal style. He famously wore a brown derby hat, apparently inspired by Al Smith, the Catholic governor of New York who lost to Herbert Hoover in the 1928 presidential election.

Thorpe was a master campaigner, and his talent made him a member of the House of Commons by the time he was 30, and leader of his party seven years later. Over the course of his career he became a leading progressive in England, helping to found Amnesty International, speaking out passionately against Ian Smith’s racist minority rule in Rhodesia and apartheid in South Africa.

A Not-So-Secret Secret Life

In 1968 Thorpe married Caroline Allpass and they had a son, Rupert. Caroline was killed suddenly in a car crash in 1970. The tragic events raised Thorpe's public profile enormously; the widower with a young son earned broad public sympathy.

In 1973 Thorpe married Marion Stein. Also known as Lady Harewood, she was the divorced wife of the Earl of Harewood, Queen Elizabeth's cousin, and a concert pianist.

Though Thorpe was leader of his party, his relationships with men were apparently a thinly guarded secret in London. According to a 2015 biography, Thorpe "boasted to friends that he had seduced TV cameramen, footmen at Buckingham Palace receptions, even policemen on duty at the House of Commons. He played with fire by sending compromising letters, often on House of Commons stationery. At the time of Princess Margaret’s wedding to Anthony Armstrong-Jones, Thorpe sent a friend a postcard: 'What a pity about HRH. I rather hoped to marry the one and seduce the other.'"

It was a dangerous time to be gay. While there was some grassroots support for the LGBTQ community, and a 1967 act had decriminalized homosexuality, same-sex relationships were still widely reviled in the era. Thorpe's Liberal party supported continued changes to the laws, but the Labour and Conservative parties would have little to do with the nascent gay rights movement.

Norman Scott

Scott, also known as Norman Josiffe, is widely described as a "stable boy and aspiring model," claimed that he and Thorpe had a brief fling in the early 1960s. He said Thorpe had treated him badly, and threatened to go public with the affair, which Thorpe denied until his death.

Newspaper headlines in 1976 were the first public account of Scott's accusations. He was appearing in court on fraud charges and said "I am being hounded by people the whole time just because of my sexual relationship with Jeremy Thorpe."

It later surfaced that Thorpe's close friend Peter Bessell (played by Alex Jennings in the series), also a former member of Parliament, had given Scott £2,500. Those funds, it turns out, were supplied by David Holmes, a wealthy banker and a deputy treasurer of the Liberal Party. Thorpe's scandal had ensnared his friends, his career, and his party's leadership.

Grant noted in an interview with T&C that A Very English Scandal doesn't delve deeply into Thorpe's convoluted financial dealings. "Thorpe was very dodgy on money," says Grant. "If you talk to all of those Liberal politicians to this day, they say the thing that made them never want to have anything to do with Thorpe again was not being gay, was not trying to kill someone—it was the money."

Accusations of Murder

Holmes had apparently hired a man named Andrew Newton to take out Norman Scott. In October 1975, Newton surprised Scott on a country road and shot his dog, Rinka. He claimed he lost his nerve—or maybe his weapon jammed—and couldn't shoot Scott. Newton was later convicted of firearms charges and sentenced to two years in prison.

Thorpe tried to quell the brewing furor over his rumored relationship with Scott by releasing some letters he'd written to the younger man in the early 1960s. Meant to prove that they were merely friends, the letters did just the opposite. One of of the notes became known as the Bunny Letter because of Thorpe's sign off: “Bunnies can (and will) go to France. Yours affectionately, Jeremy. I miss you.”

Thorpe was forced to resign as leader of the Liberal Party in 1976.

The Trial

Thorpe's troubles weren't over. Gunman Andrew Norton was released from prison in October 1977 and told the Daily Mirror that he had been paid £5,000 to shoot Scott. The police investigated, and in 1978 Thorpe, Holmes, and two acquaintances named John Le Mesurier and George Deakin were charged with conspiracy to commit murder.

The trial was no less controversial than the crime. The judge's sympathies clearly lay with the patrician Thorpe, and he told the jury that Scott was "a hysterical, warped personality… a neurotic, spineless creature, addicted to hysteria and self-advertisement." He maintained that none of the witnesses—Bessell, Newton, or Scott—could be trusted because they stood to gain by selling their stories to the eager press.

Thorpe and his co-defendants were found not-guilty.

To T&C, Grant described the difficulty of playing a character whose guilt or innocence wasn't clear—despite his acquittal. Grant spoke with several of Thorpe's friends and colleagues and discovered no consensus.

"What was amazing was the disparity," said Grant. "I talked to people who said, 'Jeremy would never hurt a fly. It is disgusting to even think that he could have ordered a murder or anything.' And I also spoke to people who also said, 'Oh, he was a monster.' There I was trying to get a sense of the guy, and in a way I think that was the answer; he was capable of giving all those impressions."

The Aftermath

Thorpe's political career was over with the trial. He was voted out the year of his acquittal in the election that brought Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party to power. He retired with his wife, Marion, and died of Parkinson's Disease in December 2014. Marion had died just months before him.

Rupert Thorpe, Jeremy's son, is a photographer and lives in Los Angeles. Grant says he chose not to meet Rupert when working on his portrayal of Jeremy. "I just thought it could go all wrong. I thought it was better to keep my distance a bit."

Norman Scott, now 78, lives with his dogs and his boyfriend in Devon, England.

Elizabeth Angell is the Executive Editor, Digital for Town & Country, where she writes about the British Royal Family, the Kennedys, Ivy League shenanigans, superstars of interior design, and trends in style, beauty, and home.